Selected Artworks

SCHERMO - DISEGNO VERTICALE / ORIZZONTALE, 1957

Tempera on paper

70 × 100 cm

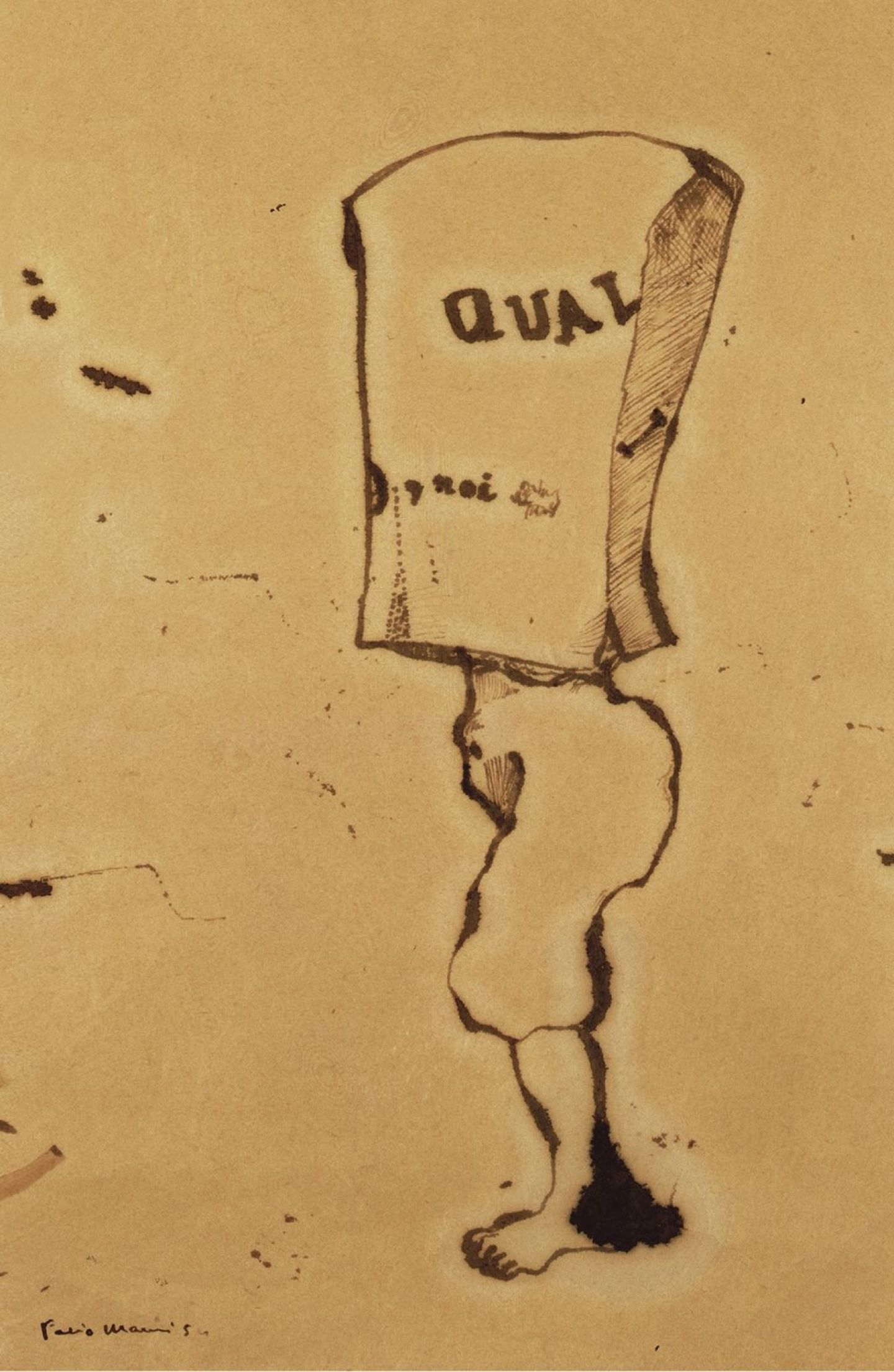

UN UOMO QUALUNQUE NEL SACCO, 1954

Ink on paper

27 × 20 cm

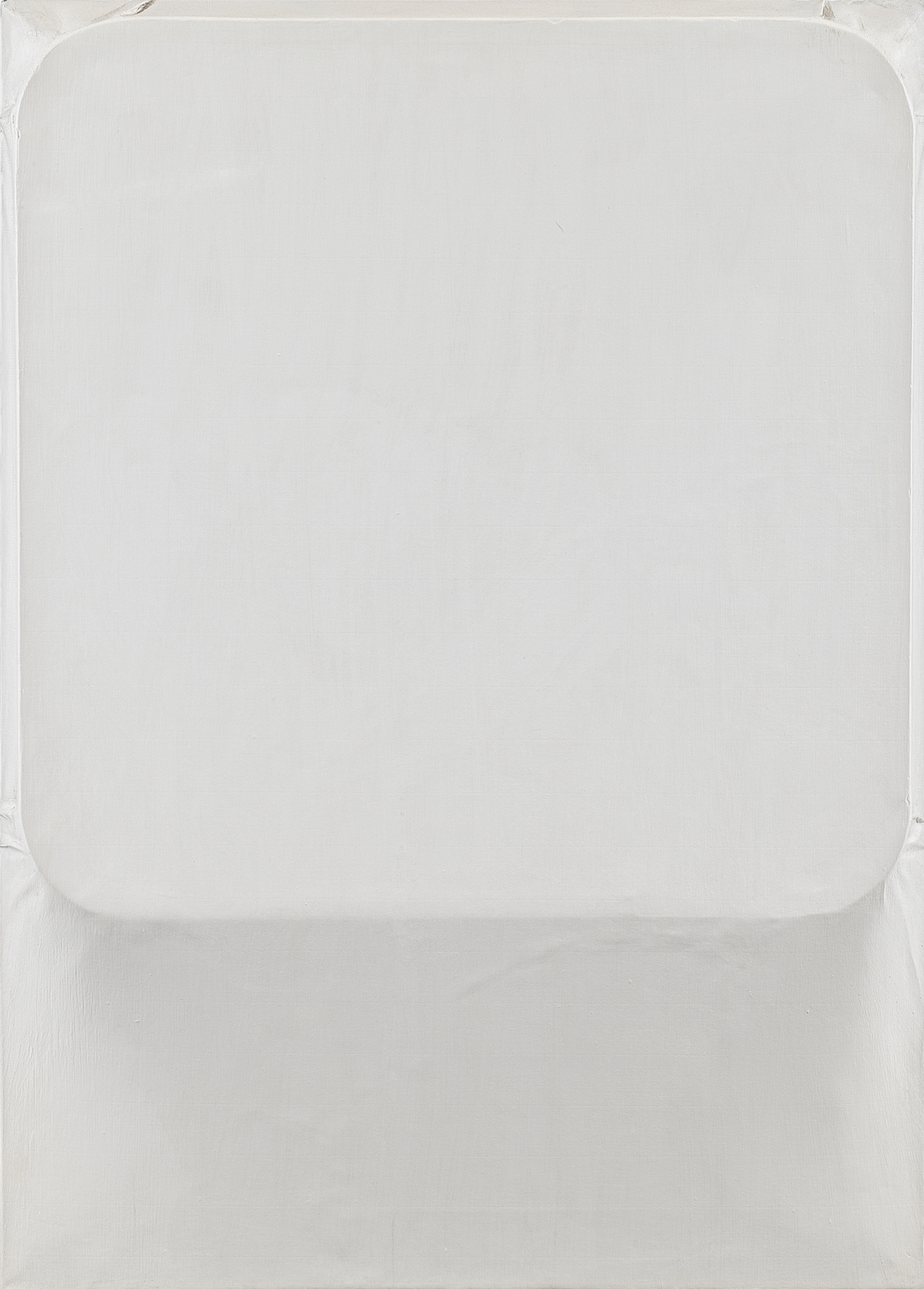

SCHERMO, 1958-1959

Painted canvas on protruding frame

60 × 43 × 5 cm

Mauri’s Schermi are of two types. The Schermo-Disegno on paper echoed the film format, consisting of a black frame that, painted along the edges of a sheet of paper, mapped out a field for projection; the other type, using overhangs, consisted of wooden frames shaped like television sets of the day, over which he stretched paper or, later, fabric.

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev writes that Mauri was a forerunner of “an artistic, sociological and philosophical debate around communication theory that would develop in the 1960s after his early, precocious reflections. From the very beginning, for Mauri the work was a ‘second-degree work,’ a meta-work that conveys the experience of reality in a meta-real way, intended as a critical deconstruction of thought-manipulating mechanisms, as well as exploring identity of subject in a complex age of experiences pre-determined by narrative, filmic and comic book representations, not to mention all other contemporary ideological apparatuses.”

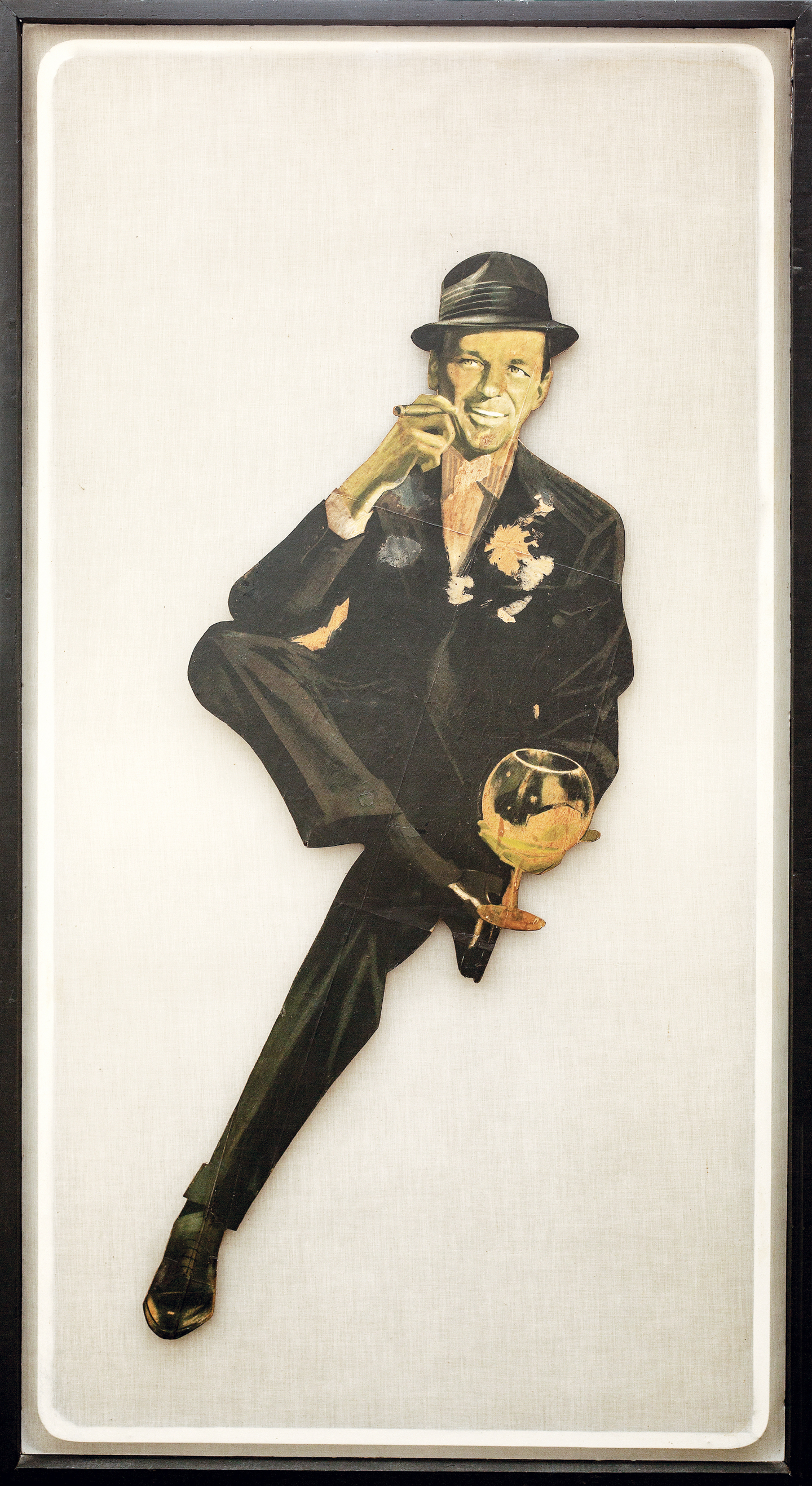

SINATRA, 1964

Print on shaped wood, canvas on protruding frame, 186 × 100 × 6 cm

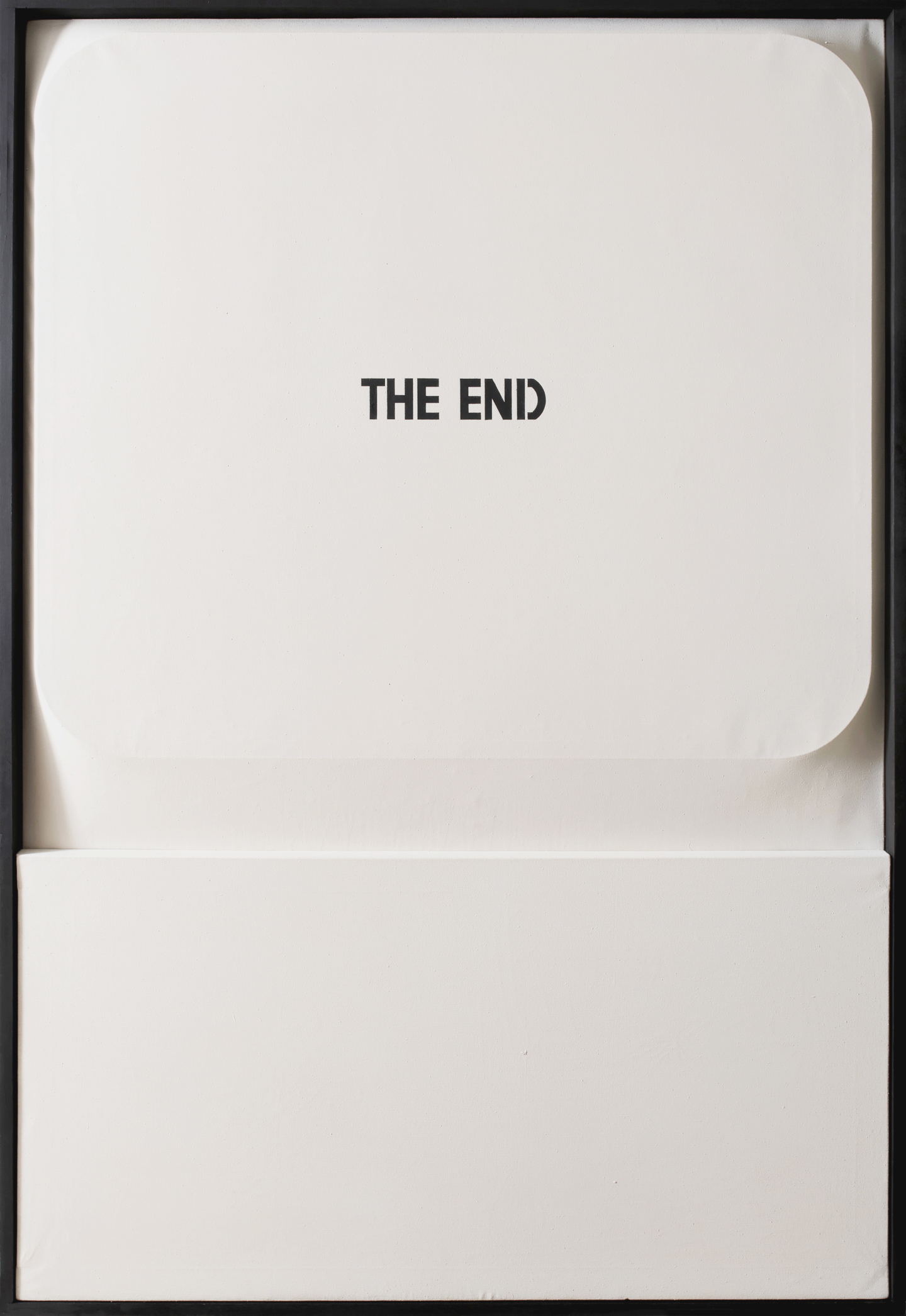

THE END, 1970

Enamel on canvas on protruding frame

225 × 150 × 8 cm

The artist’s tendency to use objects in composing his works first appeared in early paintings displaying typical consumer society products within drawers and wooden boxes, in something of a Neo-Dadaist layout aesthetic.

Sculptures from this period distinctively used electric light, introducing the theme of the physicality of the ray and projection as a metaphor for thought, as in Pile and Cinema a luce solida (1968), produced by the Mana Art Market Gallery in Rome.

CASSETTO, 1960

Purchased objects in wooden drawer, 60,4 × 74,8 × 10,2 cm

CINEMA A LUCE SOLIDA, 1968

Methacrylate sculpture, electric light, 170 × 74,5 × 68 cm

The installation Cinema a luce solida [Solid light Cinema], realised in 1968, consists in a projector made of plastic and neon lights. It reminds us of the “Lampadine con i raggi solidificati” by the two Futurists Depero and Balla.

With his work, the artist gives concrete form to the idea of “projection”, he transforms light into a solid body.

He moves from the assumption that in life everything, including the thought, is real. The corporeality of the projection here anticipates the further development that this idea will have in the cinematic reflection of the Screen and the Projections. It is a metaphor of the relationship between mind and world, between the memory of things and their recognisability and evolution.

Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 62.

Mauri made his debut in the theatre world in 1958, writing and directing the play Il Benessere with Franco Brusati. Staged by the Teatro Stabile di Roma, it was later translated into French and retitled Flora.

In 1960, Mauri wrote his most significant play, L’Isola, a pop-art inspired comedy conceived as a collage of literature, theatre and comics. The play premiered in Spoleto in 1964; two years later, it was staged in Rome.

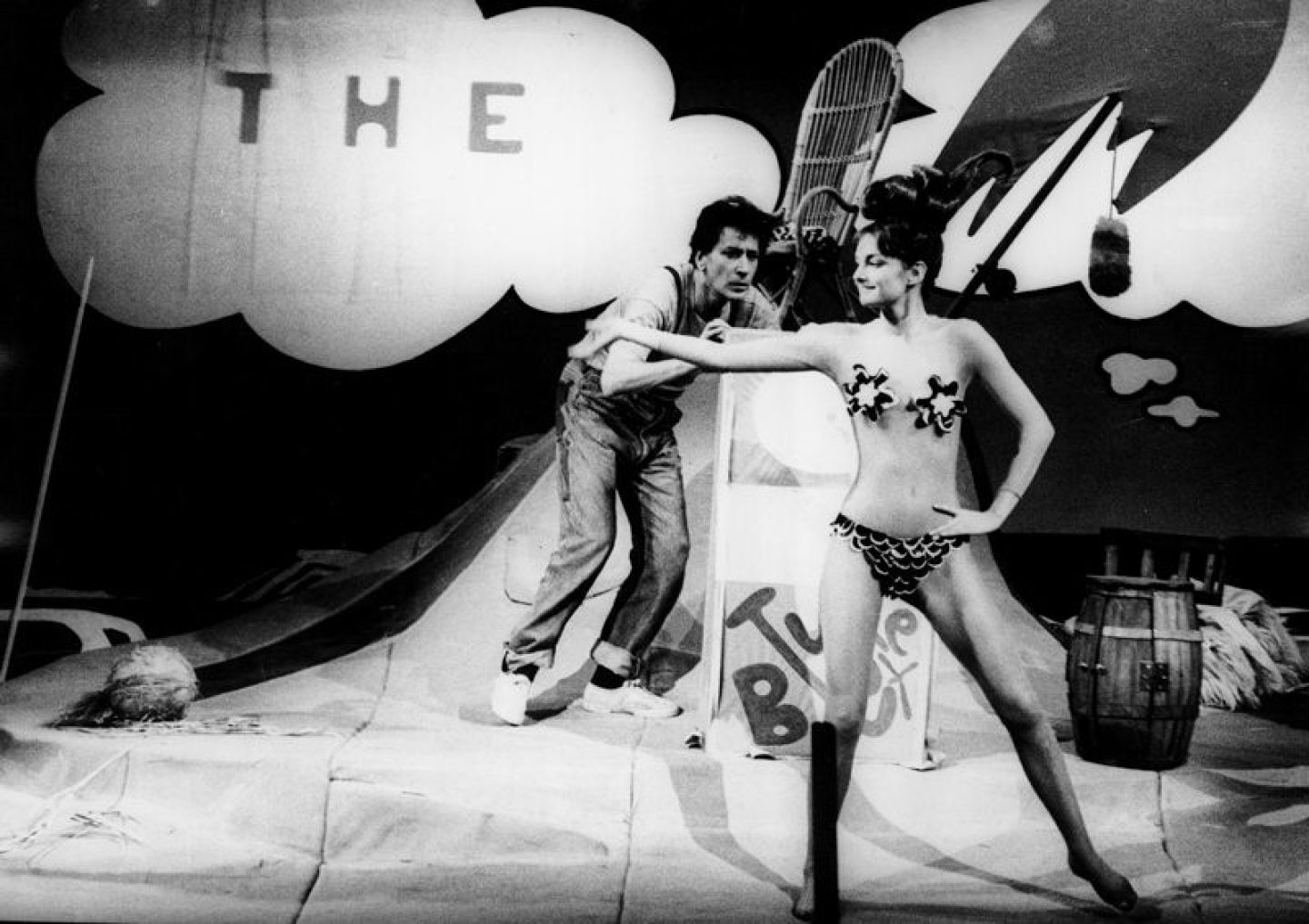

L’ISOLA, 1964

Theater play written, designed and directed by Fabio Mauri

The play L’Isola [The Island], written in 1960 and performed at the Teatro Stabile in Rome in 1966, is a monologue in two acts and two scenes with Alberto Bonucci and Rosemarie Dexter, music by Gino Negri.

The date, set, costumes and structure of the play clearly refer to the use of comic books as new popular code. The plot is a delirious stream of consciousness and imagination brought on stage as if it were an art exhibition. The use of the materials is highly indicative: yellow canes, white bear fur, black rubber, jeans. Nothing is faked. All the objects are used on stage as expressive material. The actors, like animated characters of a comic book, use the easy language of comic strips, which are, in their own way, sophisticated and often surreal and which the average man has been used to since his childhood.

Mauri’s first installations – work-environments with active viewer involvement – date back to the mid-1960s. In chronological order, Foto di cinema come affresco (1964) – a contemporary chapel at which, rather than sacred frescoes, he presented Hollywood faces – preceded Luna (1968) by four years. In Luna, visitors were invited to plunge into a space-like environment with black walls and a floor of white Styrofoam particles. Conceived for Il Teatro delle Mostre at La Tartaruga Gallery in Rome, the work was subsequently shown at the Vitalità del Negativo exhibition in 1970, as well as at many other venues.

LUNA, 1968

Wood, polystyrene, black canvas, and brooms

496 × 885 × 530 cm

Luna [Moon], presented in 1968 at the Galleria La Tartaruga as part of the “Teatro delle Mostre” (a cycle of exhibitions conceived by Plinio de Martiis), Mauri recreates a moonscape, anticipating of six months the landing of the Apollo 11.

Two layers of polystyrene placed underneath a multitude of white beads make the floor soft, and the visitors have the feeling of walking on a thick layer of compressed material.

The moonscape is accessed through a hatch, and visitors can move, lie down, sit or swim in this sea of polystyrene.

Light, reflected on the white surface, creates a new, cosmic atmosphere.

Children, some of which grew up to become museum directors, used to beg their mums to go to the gallery and play inside the Moon.

Fabio Mauri made his performance debut in 1971. His actions Che cosa è il fascismo and Ebrea contextually raised the curtain on this cycle of ideologically based works.

Unlike most performances of the day, which tended to focus on the body and the artist’s figure, Mauri’s performances were distinguished by a fundamentally different approach. Unaffected by artist-performer protagonism, he lurked behind the scenes, directing the show. Influenced by Mauri’s previous experience as a theatre director, this characteristic should primarily be interpreted as a consequence of pictorial research that sought to go beyond the limitations of representation; similar to the painter, the artist composed a scene while remaining outside it: “For me, a performance is a logical evolution of painting, a collage of living objects.”

One exception to this was Il televisore che piange (1972), a happening that he created for Italian national television. Reaching into millions of people’s homes, the action consisted of a TV programme suddenly being interrupted, the screen turning white, and a weeping man becoming audible in the background.

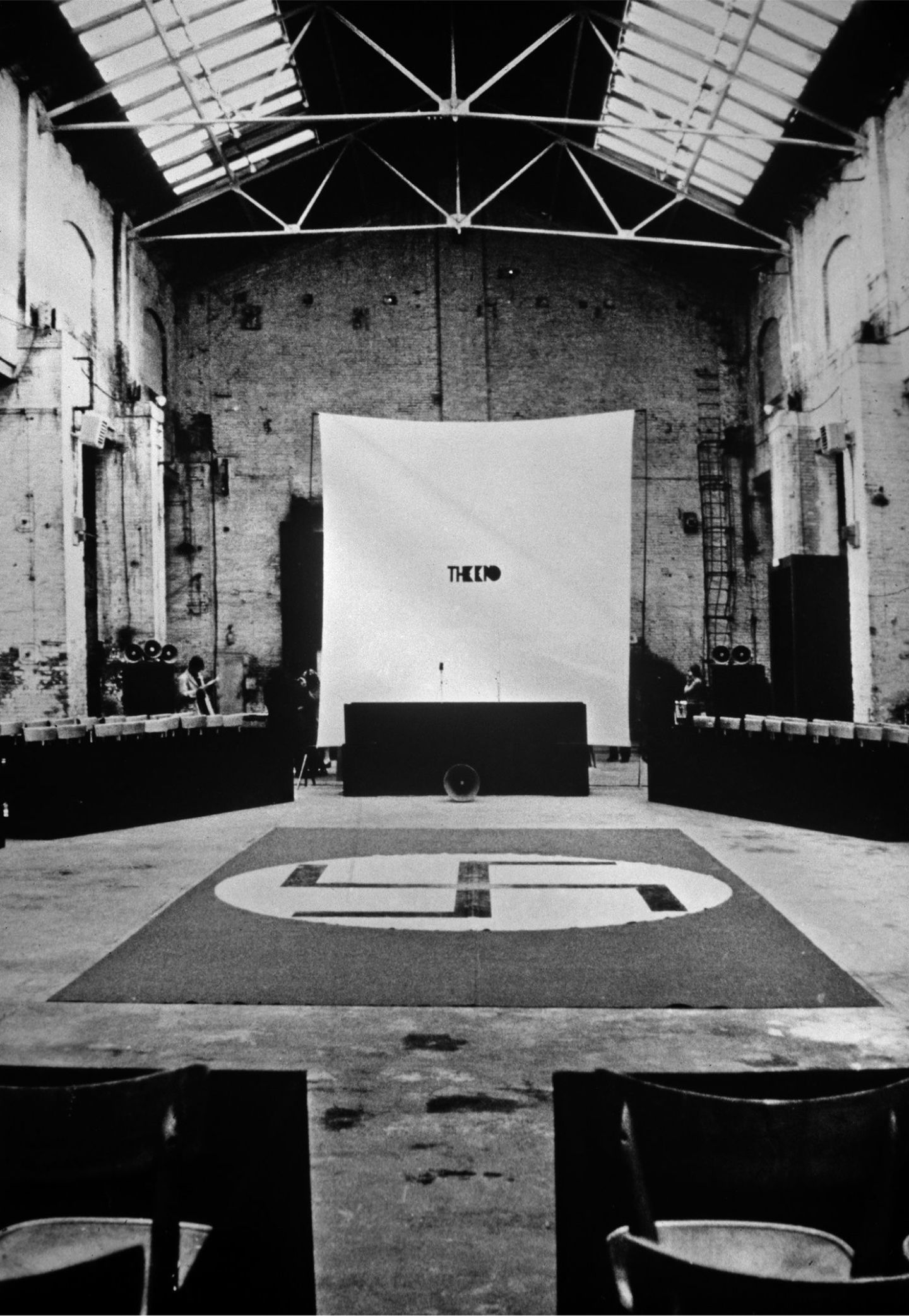

CHE COSA È IL FASCISMO. FESTA IN ONORE DEL GENERALE ERNST VON HUSSEL DI PASSAGGIO PER ROMA, 1971

Performance

The memorable performance Che cosa è il fascismo [What Fascism is] debuted at the Safa Palatino Film Studios in Rome on 2 April 1971. The students of the Accademia Nazionale d’Arte Drammatica “Silvio D’Amico” took part in the performance, which concludes the series of lectures “Gesto e comportamento nell’arte oggi” [Gesture and behaviour in today's art] given by Giorgio Pressburger. The inspiration is the revival of Hitler’s visit to Florence in 1938, on occasion of which the Bologna team, of which Fabio Mauri, his friend Pier Paolo Pasolini, Fabio Luca Cavazza and others were part, wins the intellectual youth games. The work consists in the re-enactment of the “Ludi Juvenales”. They are followed by calisthenics, fencing fights, ice-skating performances, parades of flags, national anthems and debates on Fascist mysticism. The action takes place on a red rectangular carpet with a swastika in the middle, set between black stands subdivided by guilds (Artists, Experts in Agriculture, Experts in Construction, Engineers), and the audience is invited to take a sit. Two small sets of stands bear the star of David, symbol of the racial discrimination that took place during Fascism and that was presented to be harmless and natural. The invitations to the performance, of different colours according to the social class they are for, are handed to Jewish men and women, for whom the small sets of stands are destined. Music from the Fascist repertoire precedes and accompanies the ceremony, which is occasionally imaginary, only evoked from the Podium from which the Gioventù Italiana del Littorio [the Italian Youth of the Lictor] is directed.

At the end of the competitions, the Luce movies are projected onto an old screen: these are historical newsreels filled with the obviously fake news of the Fascist propaganda. In Che cosa è il fascismo, the contrast between the apparent normality of the events and the presence of negative signals creates a sense of growing uneasiness and highlights the impudence of the Lie of the Regime, as well as the unjustified optimism of a nation - or better, of two.

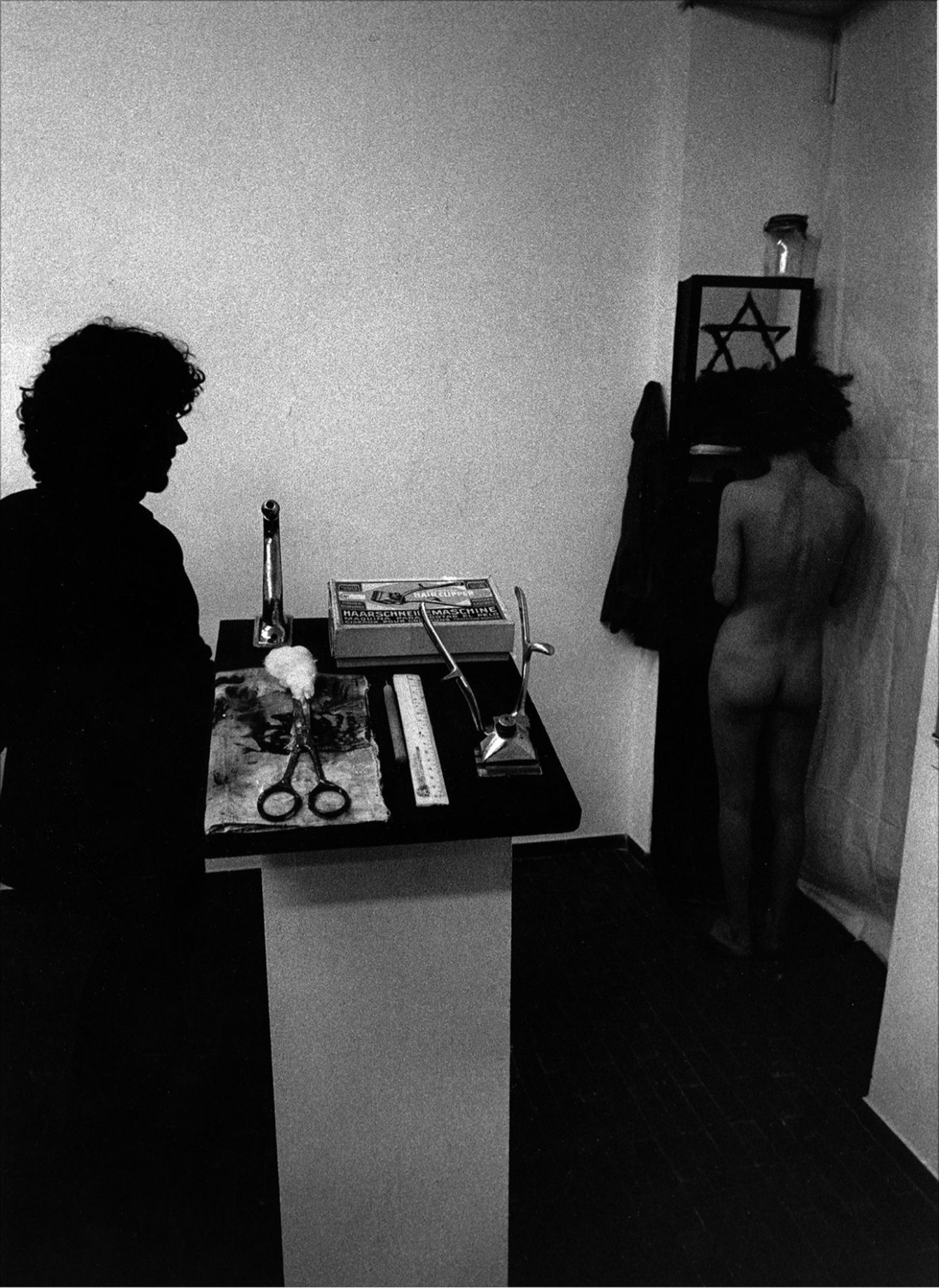

EBREA, 1971

Performance

Ebrea [Jewess] debuted in October 1971 at the Barozzi Gallery in Venice.

An unusual collection of object-sculptures introduces the ordinary elements of every-day life.Their titles, carved into metal plaques, reveal the grave nature of the objects that pretend to be of human origin: Jewish teeth, skin, hair, bones.

Furio Colombo and Renato Barilli present Mauri’s exhibition.

Work of art among works of art, the protagonist of this sacred scene is a young woman who chops off locks of her hair and uses them to draw a Star of David on the mirror in front of her. The same symbol is also branded on her chest, along with a number: the mark of racial discrimination.

The artistic expression of these works clashes with the horrific reality which is evoked.

Ebrea has an explicit and radical ideological connotation, with a strong accent not only on the negative aspects of Nazi German, but also - in a different measure - on the entire European culture that, for enigmatic, almost mysterious historical reasons that still require an in-depth analysis, did not react strongly nor promptly.

Dora Aceto in Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 96.

Photo: Claudio Abate, 1971.

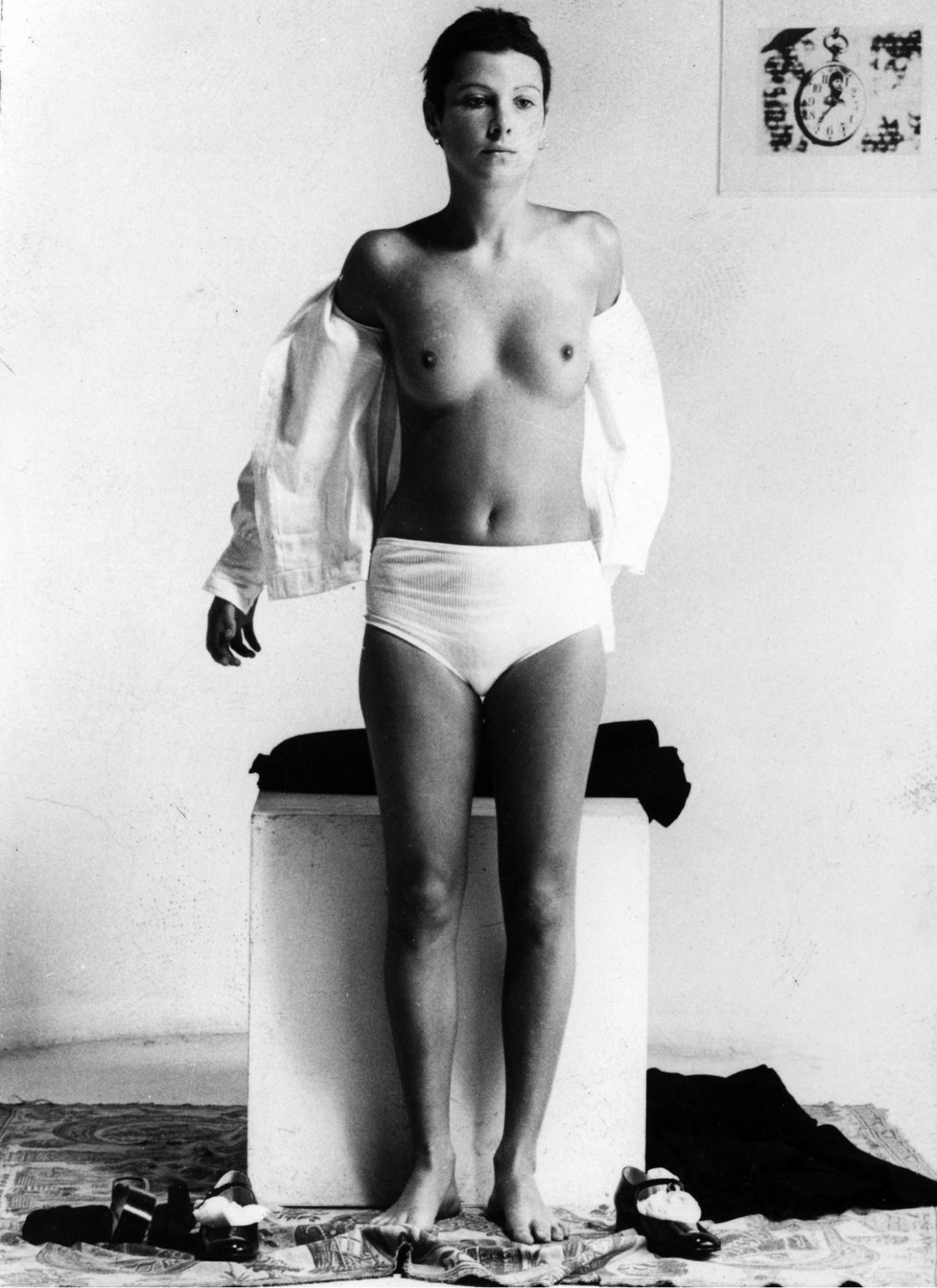

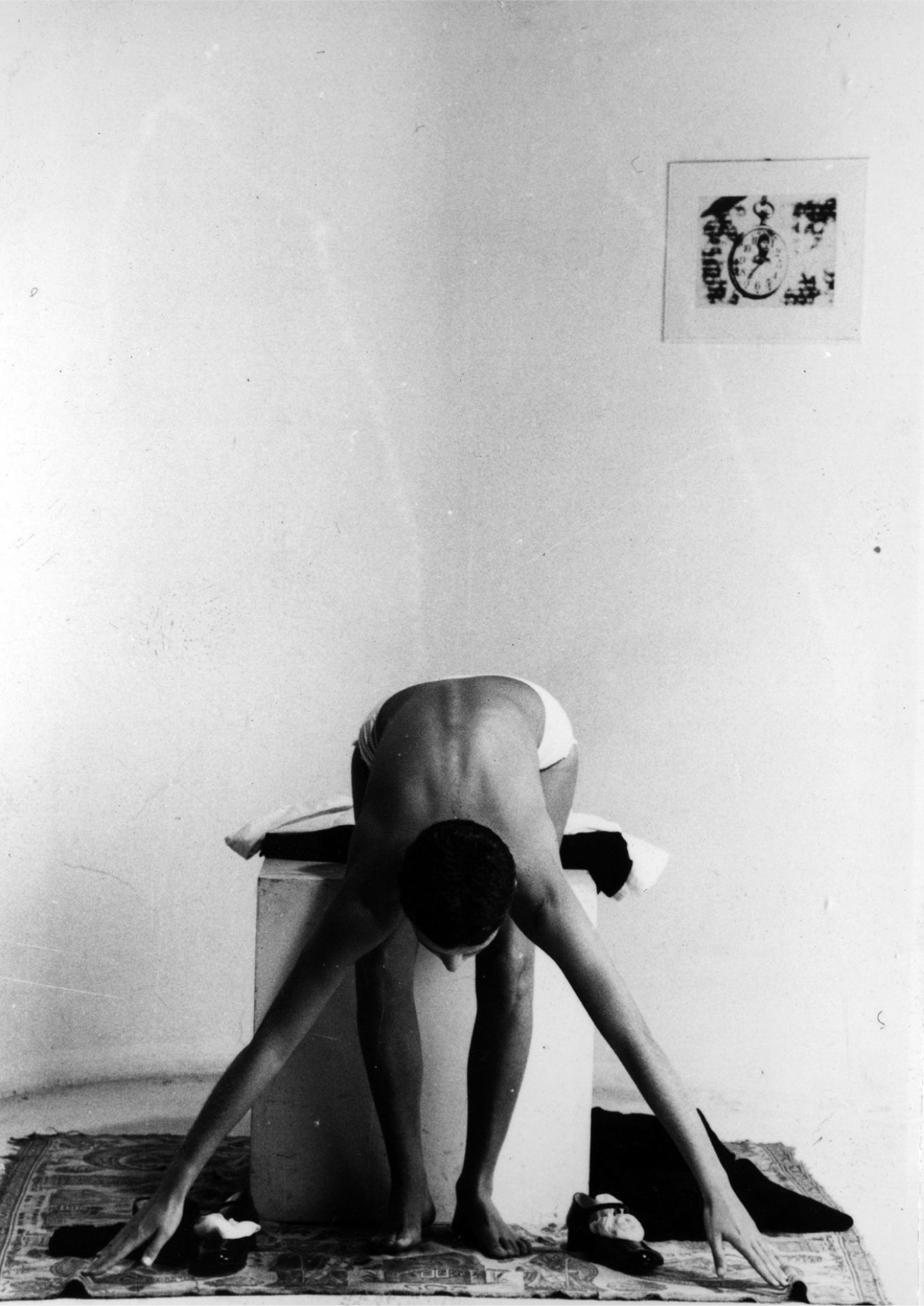

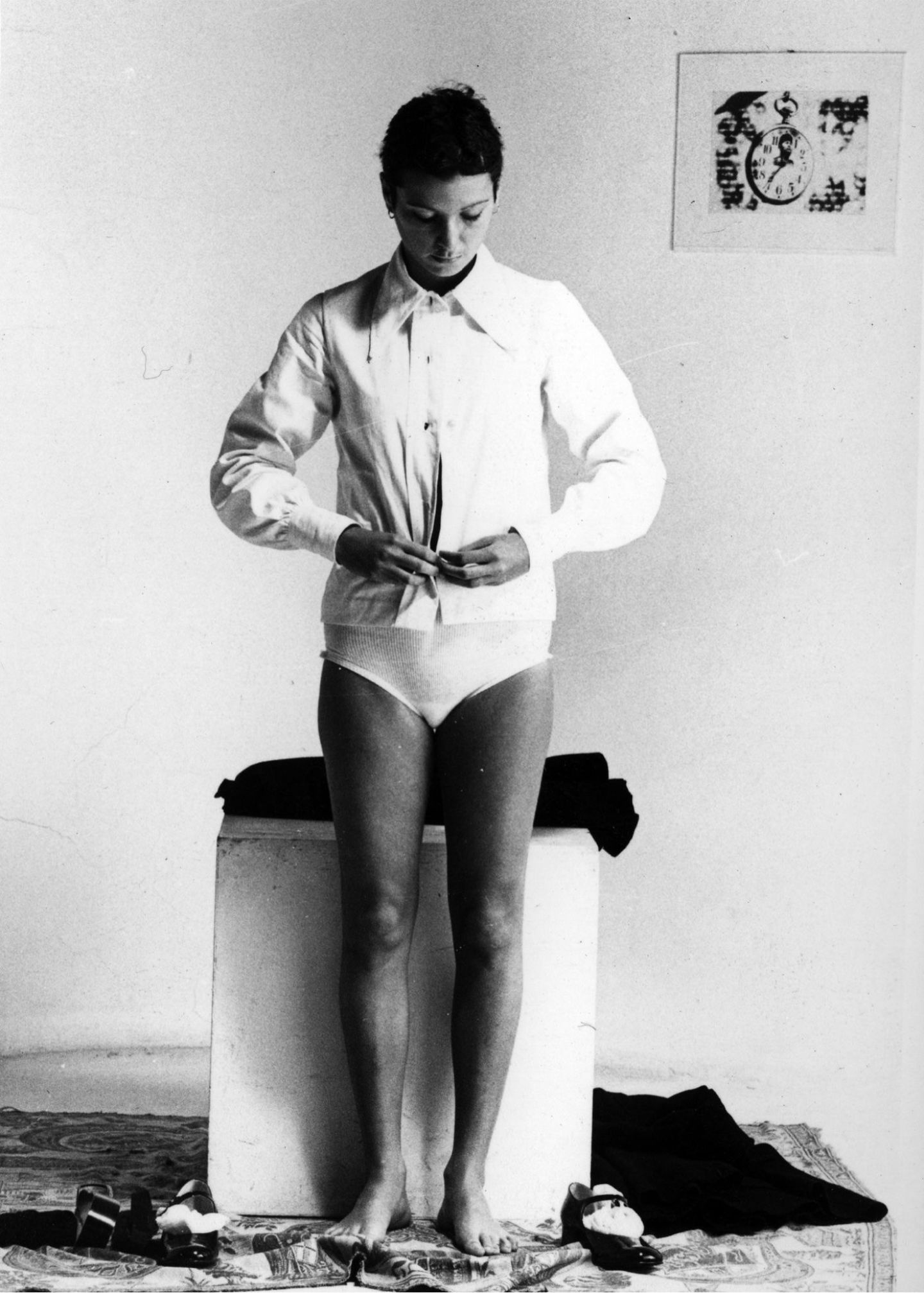

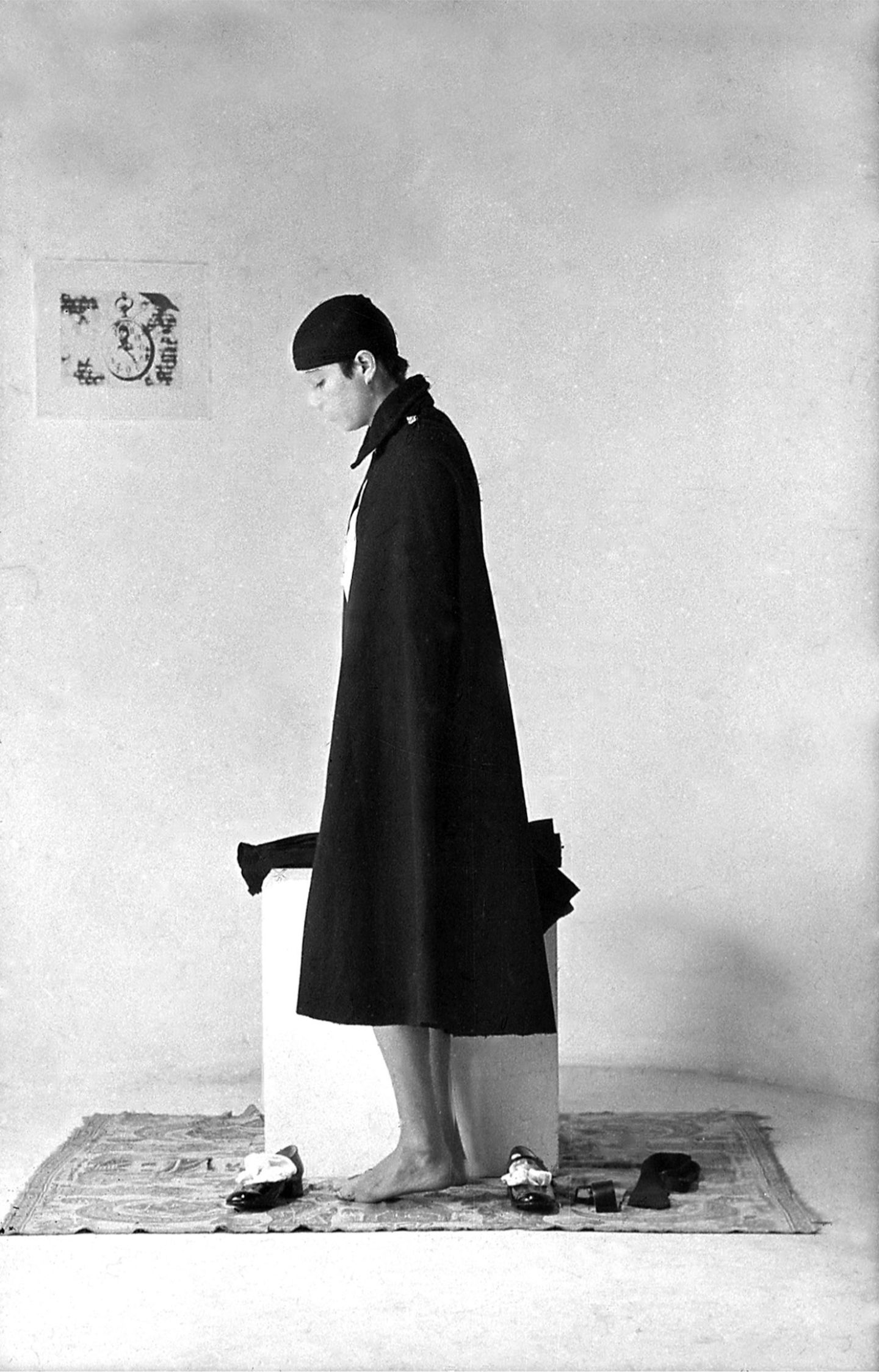

IDEOLOGIA E NATURA, 1973

Performance

Ideologia e Natura [Ideology and Nature] is a performance presented at the Galleria Duemila in Bologna in 1973.

A young girl continuously takes on and off the fascist uniform of the “Young Italians”.

First she is standing in front of a white cube, and performs this “undressing/dressing up” in a very natural and spontaneous way; then, following the rhythm given by a metronome, she starts proceeding in a more logical order.

The different ways in which she wears the same clothes every time change the ideological value of the uniform, and make the viewer wonder why she is wearing them in such an unusual way.

Her image changes according to her imagination and to the inventive and random ways in which she wears the uniform: from a Ku Klux Klan member, to Harlequin, to a member of the circus.

This journey towards a symbolical nudity highlights how the only real fact is nature, which prevails on every outfit imposed by culture or by the current ideological imagination.

Dora Aceto in Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 122.

Performance: Fabio Mauri (with Elisabetta Catalano).

Photo: © Elisabetta Catalano (with Fabio Mauri).

IL TELEVISORE CHE PIANGE, 1972

Happening. Format 4:3, black and white, sound, 00:03:12

The performance Il televisore che piange [The crying television] was broadcasted in 1972 during the RAI [Channel No 2] TV show “Happening”, directed by Enrico Rossetti, after some historical examples of the first American “Happening” by Allan Kaprow and others.

We see images of the author in front of a screen that says “The End”.

The broadcast is then interrupted for about 60 seconds as though for a central breakdown. In the background, a grief-stricken cry is heard. The words “The crying TV set” appear on the screen.

The camera then focuses on the message “The End”. Many viewers called RAI to enquire about the awkward and prolonged breakdown: someone was crying in the background of the empty screen.

For Mauri, that was a political cry, stricken by the daily contradictions of the Italian life.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 116.

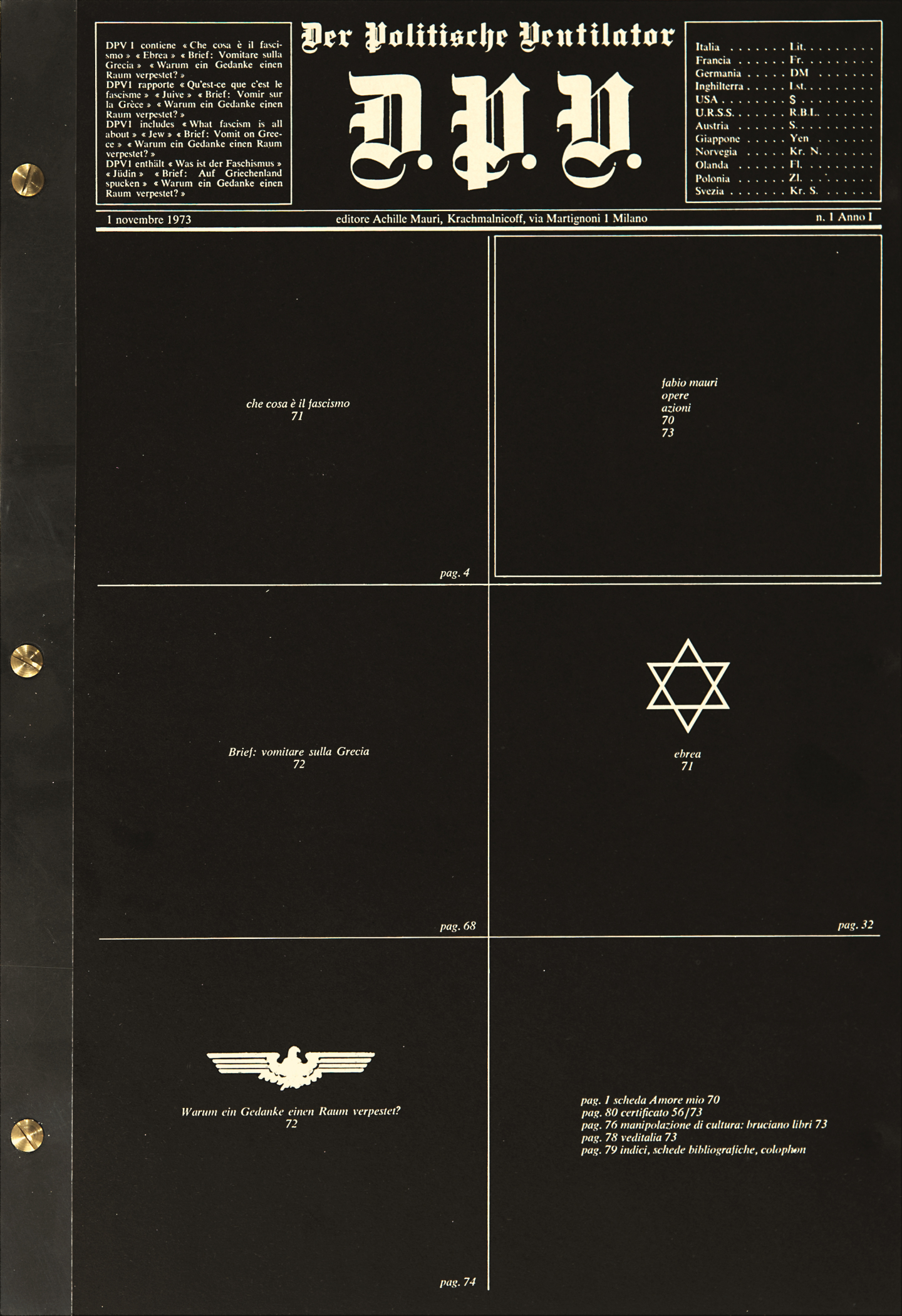

Using the artist’s terminology, what Mauri called his “political multiples” took shape in the 1970s, followed by his “social series”. Vomitare sulla Grecia (1972), Der Politische Ventilator (1973) as well as Proust (1974) and L’anagrafe (1971) were all one-off works conceived with a plan for multiples merely conceived, consistent with the practices of the Ufficio per l’Immaginazione Preventiva [Office for Preventive Imagination], at which, at that time, Mauri held the fictitious title of Rio de Janeiro office chief.

VOMITARE SULLA GRECIA, 1972

Fiberglass, rice and dried pasta in canvas paper bags

Vomitare sulla Grecia [Throwing up on Greece], the first “Multiplo Politico” [Political Multiple] realised by Fabio Mauri, is presented at the Centro Multipli of Rome in 1972. This work is characterised by a critical and political reflection on the uniqueness of the work of art, it is an artistic action aimed directly at a political target.

The artist imagines to “throw up on the Piraeus” of the colonels: he creates 500 sickness bags (like those given to passengers on board airplanes) full of resin, rice and other materials that look like thickened vomit.

Mauri is not interested in the mechanical reproduction of images: he believes that copies and multiples exist inside our thoughts and intentions, that they are more like a series of unique pieces.

“Vomitare sulla Grecia” is a political accusation expressed through a real artistic multiple, both serial (the sickness bag, the graphic) and singular (each vomit is differently placed inside the fiberglass).

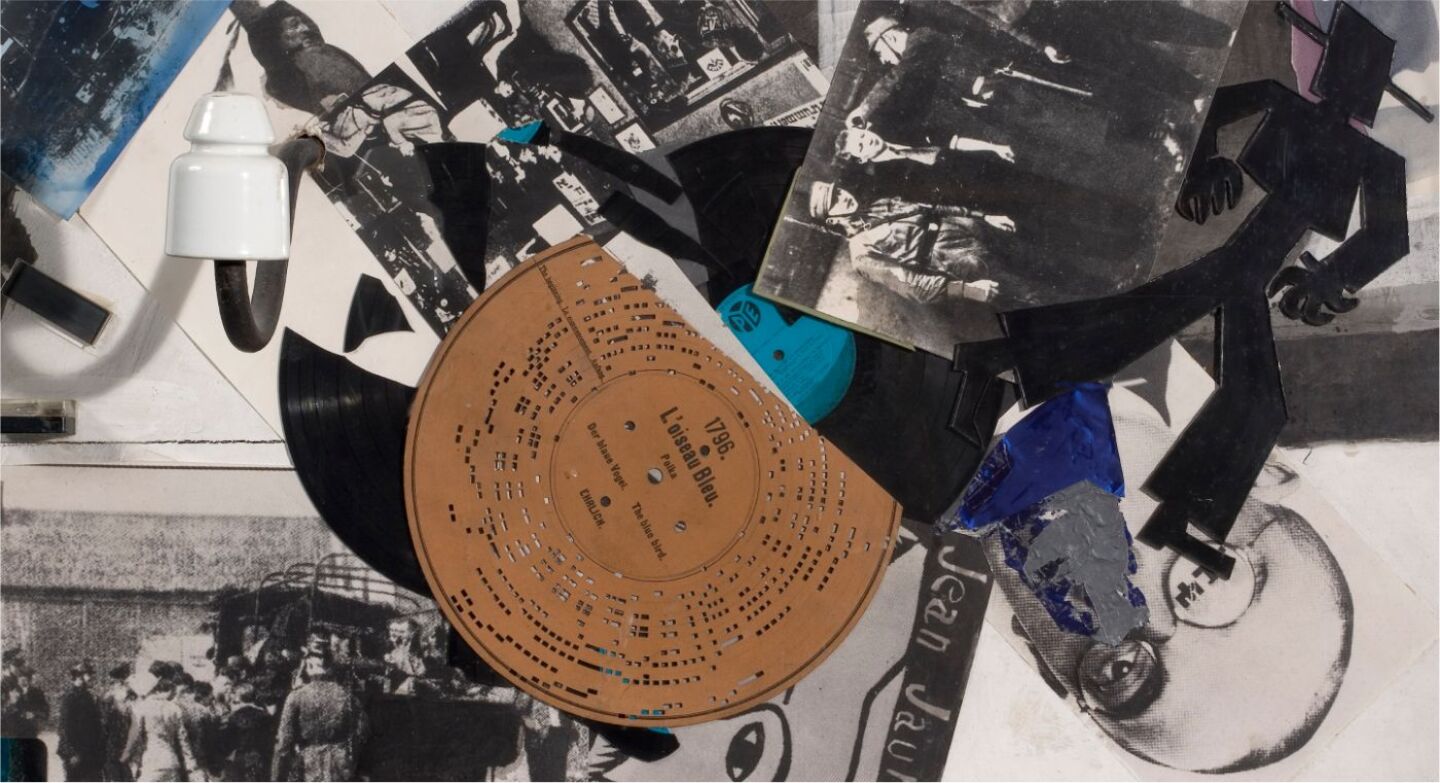

DER POLITISCHE VENTILATOR ANNO I, N. 1, 1 NOVEMBRE, 1973

Black and white illustrated book, screw binding, 40 pages, 40,5 × 28 cm

From the mid-1970s, Mauri produced a series of works involving the projection of static or moving images onto objects, environments and people.

Initiated in the 1950s, Mauri’s reflections on screens expanded to encompass the entire apparatus of film. For Mauri, its three elements (projector/beam/screen) became a metaphor for thought in the birth of meaning. The artist wrote: “In the impact between image and target, the ray (which ‘sees’ yet ‘imposes’ its own forms of intelligence) is a plausible model of the mind/world relationship. Revealed on bodies and objects, as they host it they interpret the signal received, repurposing it as a symbol, as a new metaphor. In the act of being witnessed, ensuing events generate different, subsequent, primarily formal content.”

OSCURAMENTO, 1975

Performance

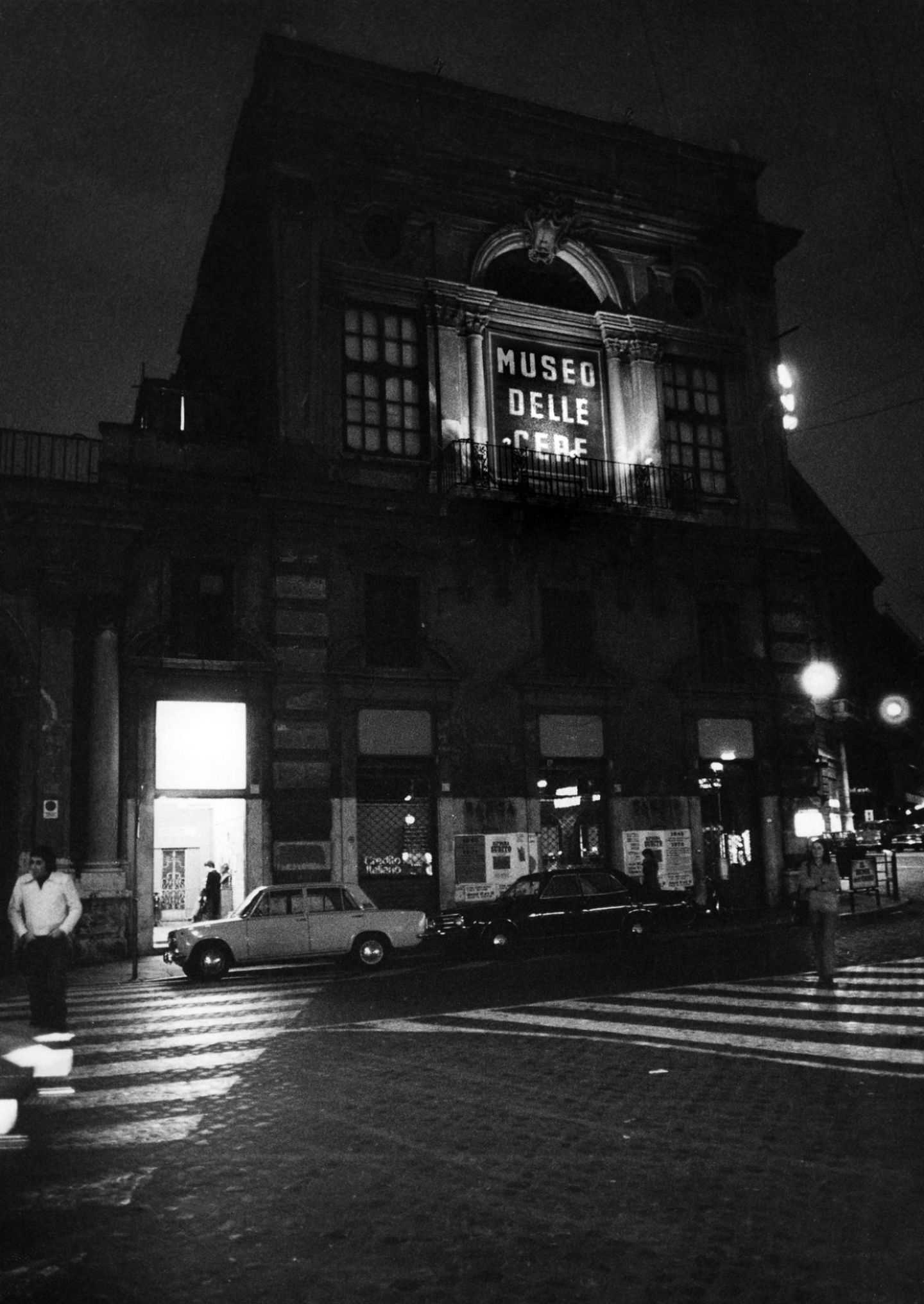

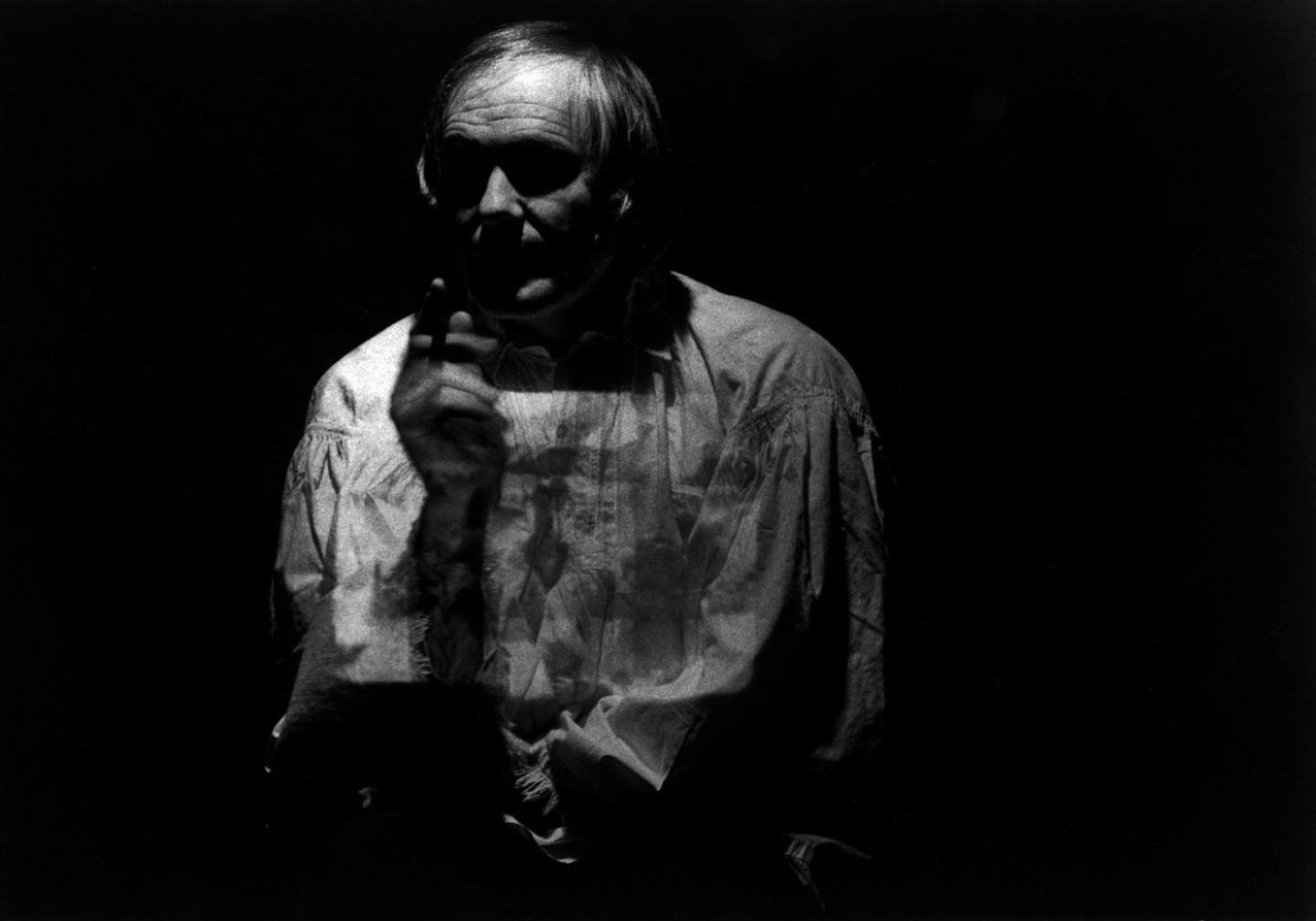

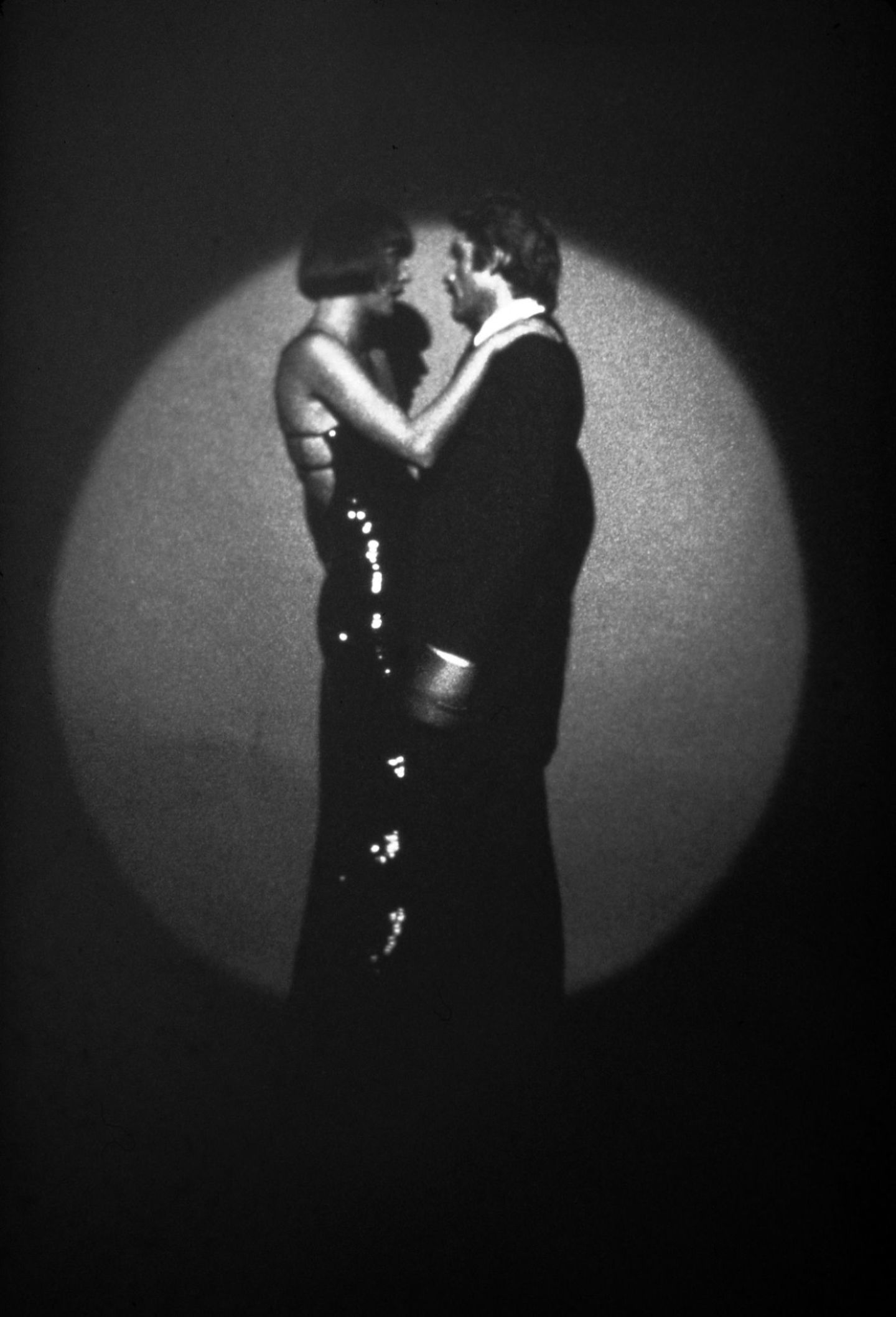

Oscuramento (Obscuring), dating back to 1975, is the reconstruction of a historical situation of uncertainty and finality, in relation to both the Great War, and to the Italian "Anni di Piombo" ("Years of Lead") and the atmosphere of death they created.

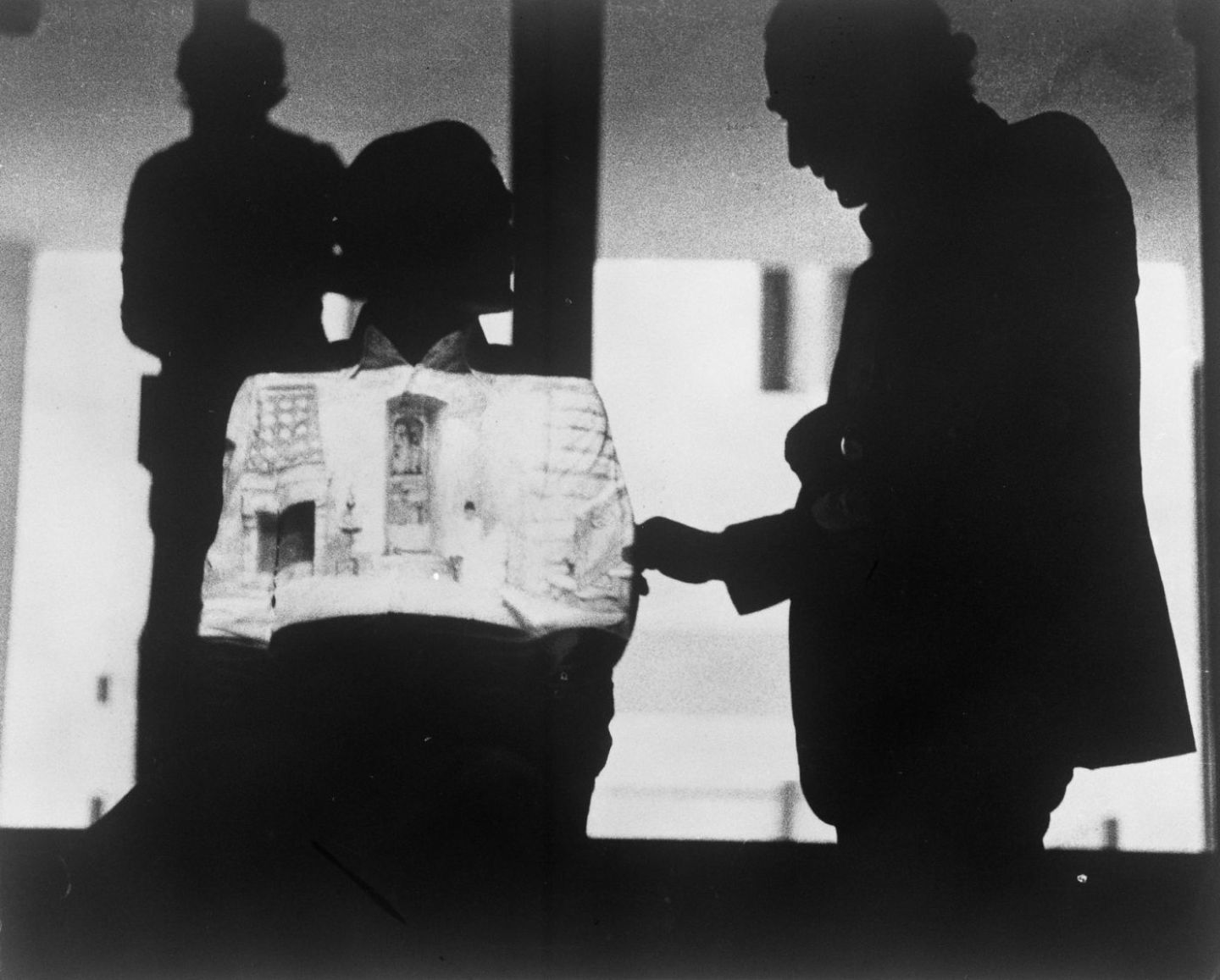

The action is arranged in three spaces and phases: the first, Intellectual, takes place in the Cannaviello Gallery in Rome. The film Red Psalm is projected onto its creator, Miklos Jancsò. The shirt of the director becomes the screen on which the film is seen, giving birth to a new meaning. Jancsò becomes the image of the character who is affected by his work and reflects it back.

History, the second phase, occurs in the Wax Museum in Piazza S.S. Apostoli. Three buses transport the public from the Gallery in Piazza Navona to the Wax Museum.

Visitors are lead into a powerful illusion, in which real actors are scattered amongst the wax statues. In a room, the singer Maria Carta performs a surreal lament, "Umbras", walking up and down an empty room. On a small platform, wax statues reproduce the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The female (wax) character is substituted for a real person (the model Dia Do Nascimento). Many scenes of the Wax Museum reproduce episodes of contemporary history that were never seen; for example, The Sitting of the Great Council of Ministers, on a proposal by Minister Grandi. The end of the Fascist Regime is being voted on.

At the end of the second phase, the public is invited to go to the study of the photographer Elisabetta Catalano, with an entry ticket with the word "Refreshment" (consumazione). Here, the third phase takes place: Obscuring, at the end of Piazza Santi Apostoli, where the Wax Museum is located.

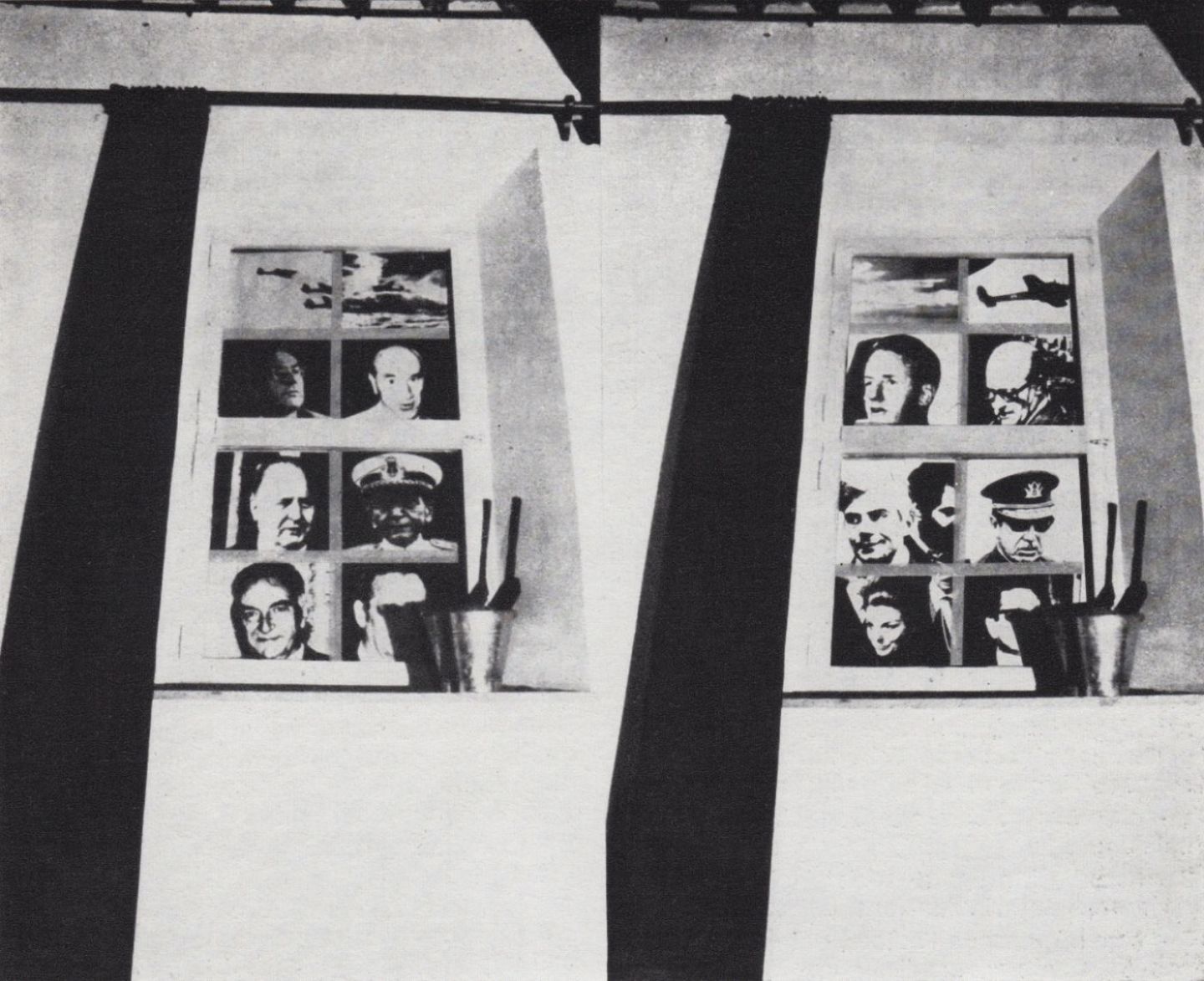

In the study, the oppressive atmosphere of war is recreated. The window panes are obscured by a series of photos of powerful and oppressive contemporary international political figures. The audience is offered a "war coffee", made of dregs, a historical drink with a specific flavour. A Vogue model and a fashion designer (Danka Schröder and Gil Cagné), exhausted, dance along to the melodies of hits from the Thirties and Forties, in a space encircled by chairs, with the jackets, the bag and the hat of the two protagonists. On a tower of metal tubes, an anti-aircraft light scans the sky and the horizon of the large studio. A remote sound of aerial bombing can be heard.

The unfolding of these events through space and time, instigates a symbolic journey back to the inner feeling of living in dangerous and dramatic circumstances, in which life is not suspended, but affected at the core, moving with great difficulty on the edge of the abyss, fruitlessly entertaining a series of tender moments: dance, music, a semblance of elegance. Joy is confined within the physical obscuring of life.

Intellettuale. Il Vangelo secondo Matteo di/su Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975

Performance with projection

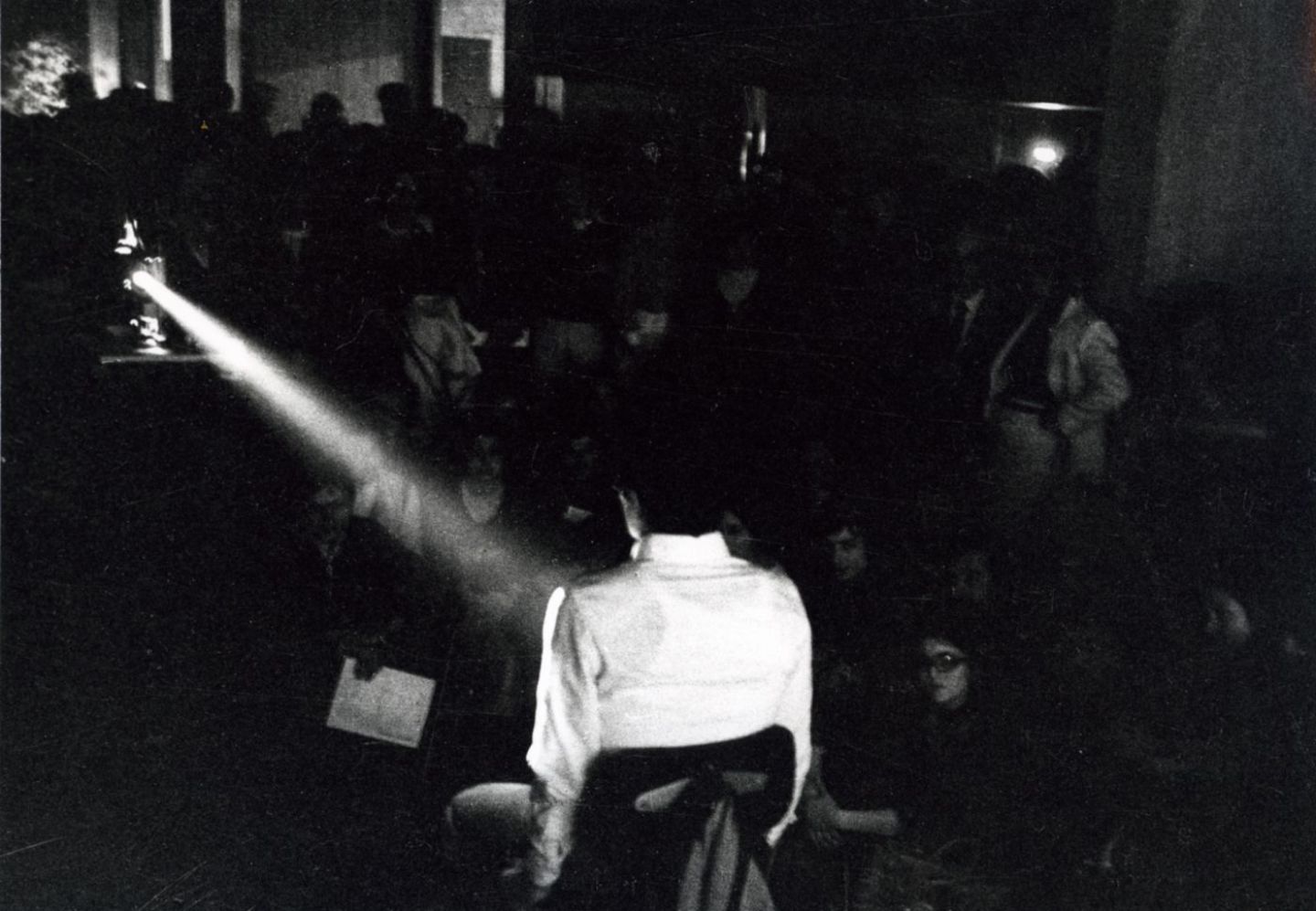

The performance Intellettuale [Intellectual] is realised for the opening of the new Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna in Bologna in 1975 with the participation of Pier Paolo Pasolini, one of Fabio Mauri’s closest friends.

The performance takes place on the stairs outside the Galleria. An exhibition on the Dada Movement curated by Franco Solmi – a movement that Mauri admires but in which he does not take part - is on display inside the gallery. Mauri, on the other hand, prefers to stage his performance outside the building. He asks Pasolini to sit on a chair, and the poet is then transformed into a “living screen”: the film The Gospel According to St. Matthew is projected on his body. The sound, too loud compared to the small dimension of the image, increases the confusion that the performance creates in the audience and in Pasolini himself. The photographer Antonio Masotti sits in the audience and takes 15 shots of the performance: these images will become famous worldwide.

The choice of projecting the film on the author himself is, according to Mauri, a way for the author of the film to become objectively responsible for his work, the effects of which he now experiences first hand. The audience was made up of Mauri’s and Pasolini’s childhood and school friends who, as the two authors, became professors, publishers, essayists - Pasolini, afraid of possible displays of affection, did not acknowledge any of them.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 160.

Photo: Antonio Masotti, 1975.

SENZA IDEOLOGIA, 1975

Projection onto milk

150 × 50 × 400 cm circa

Senza, Senza ideologia, Senza titolo [Without, Without ideology, Untitled] are some of the Projections which the artist started creating in 1975: the works consist in films projected on objects and bodies, which become witnesses to history.

The corporeality of the beam of light projected on the screen-world becomes a metaphor of the creation and the transformation of meaning and a model of the relationship between intellectual activity and reality. This physical experiment, which is also a demonstration of how languages change, is conducted in the light of the meeting and the hybridisation of realities which are all different for their connotation and ends.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 138.

Photo: Claudio Abate, 1997.

Multiple works laid out to render the idea of a room – Warum ein Gedanke einen Raum verpestet? (1973), Linguaggio è guerra (1975), Manipolazione di cultura (1976) and Entartete Kunst (1985) – were Mauri installations that often dialogued with the history of the location where they were sited. For example, Brunelleschi e noi (1977), created in the cloister of the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Umanesimo-disumanesimo (1980), which used the Fascist architecture fountain at the Florentine capital’s train station, and Quadreria (1999), conceived for Villa Medici, Rome.

LINGUAGGIO È GUERRA, 1974

Stamp on photographic reproductions on cardboard

A selection of photographs is presented, altered by cuts and montages, taken from English and German magazines.

On each photo there is a seal, with the writing "Language is war".

The frontal and symmetric composition of the image allows it to be read in slow motion, even when the subject represented is in motion, stripping the images of any possible trace of pathos. Mauri's intent is to deepen the discourse on the plurality of ideological languages that are manipulated by societies in the struggle to achieve ideological supremacy. Language is a weapon, therefore language is also war.

In 1975, these same images were displayed sequentially, as an installation, in the Foto e idea (“Photo and Idea”) event, at Parma's Municipal Museum. In 1978, in Vancouver at the Western Front Society.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milano 2009, p. 171.

Photo: Sandro Mele, 2010.

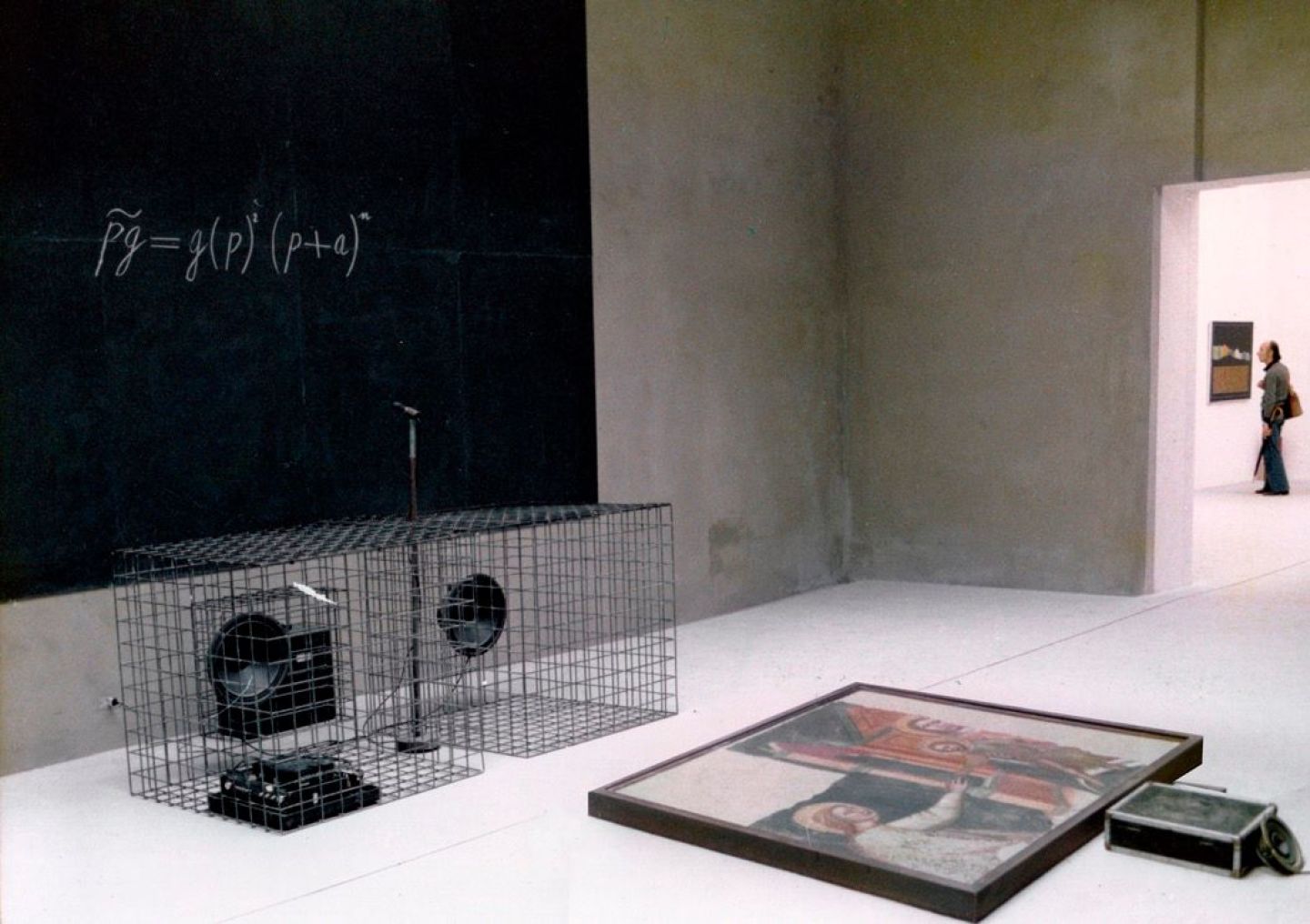

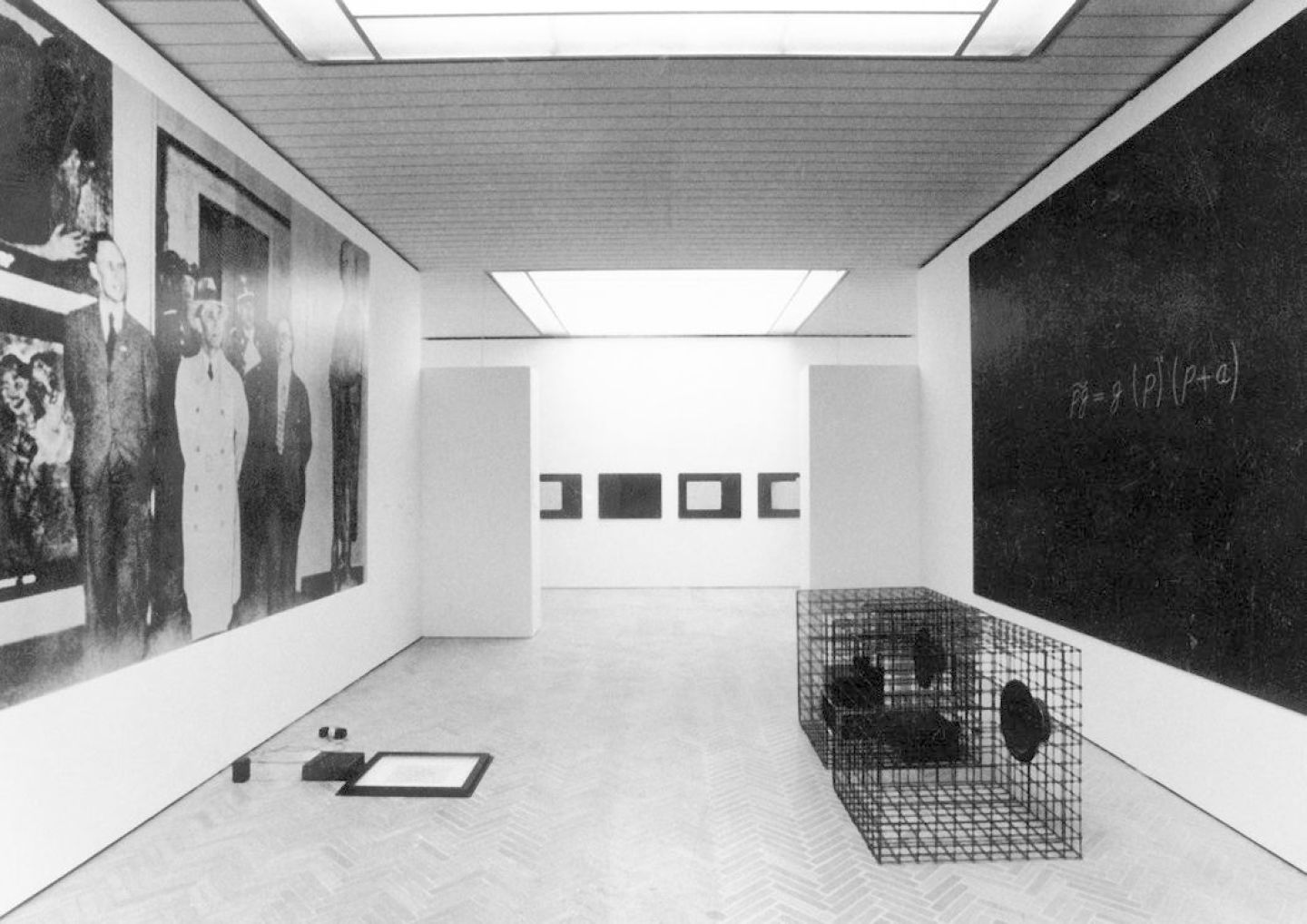

I NUMERI MALEFICI, 1978

Blackboard with chalk inscription, photographic print, metal cages, framed lithograph by Giorgio de Chirico, suitcase, sound system

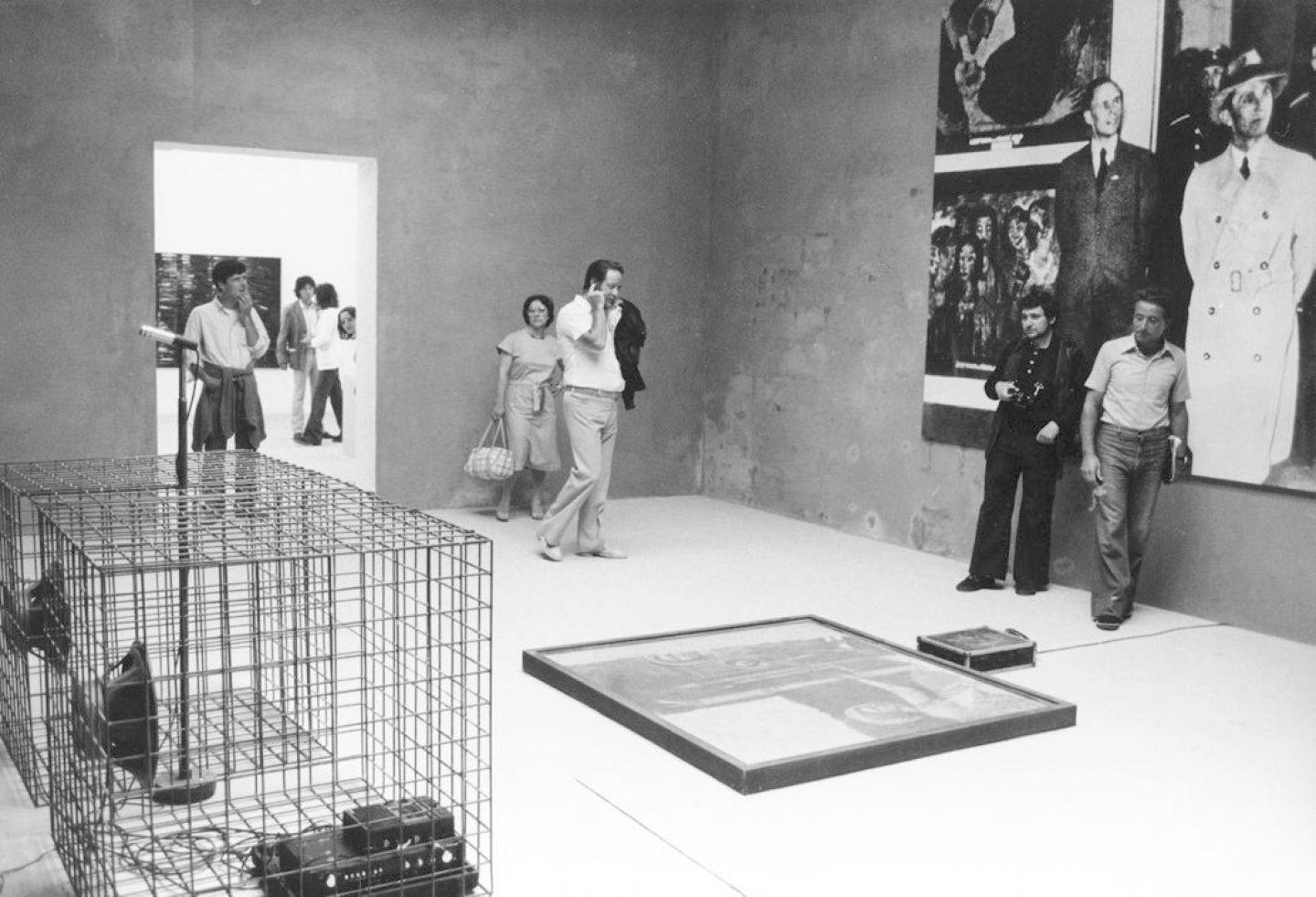

The installation I numeri malefici [Evil numbers] is presented at the Venice Biennale “From nature to art, from art to nature” in 1978. The theme of the exhibition is the critical rethinking of history: miscalculation and error of judgement are the parameters with which man and History can be interpreted.

The different elements of the room are unequivocal symbols for nature, art and criticism, whose seemingly distant paths are metaphorically connected by the hypothetical existence of a law that regulates what is true and what is wrong.

On a blackboard, Mauri formulates, with the help of the artist and mathematician Robert Klein, the numerical formula of the pursuit of the principle of mistake.

Inside two symmetrical cages, one next to the other as if they were the frame of a desk, the deep sound of an earthquake resonates from the speakers every twenty minutes.

On the floor, perhaps the only fragment existing of Lo sposalizio mistico di Santa Caterina d’Alessandria [St. Catherine of Alessandria’s mystical wedding], a mural painting by Giotto or Giottino which testifies the greatness of an artwork. The rest of the composition is on display at the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Next to the mural, a speaker from an intimidating black briefcase repeats in different languages: “What is nature?”, alternating with the sinister ticking of a timing device. In the background, the deep sound of an earthquake. In front of the blackboard, on the opposite wall, there is a picture of Goebbels and the two curators of the museum during the opening of the exhibition Entartete Kunst in Berlin.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 171.

Photo: © Elisabetta Catalano, 1978.

UMANESIMO / DISUMANESIMO, 1980

White canvas, red dye, fountain

In September 1980, Mauri takes part in the event Umanesimo/Disumanesimo nell’artecontemporanea [Humanism/Inhumanism in Contemporary Art]. Among the several options offered by the city, the artist chose the long and narrow pool of the Palazzina Reale di Santa Maria Novella.

Mauri worked with a very rationalist structure, built on occasion of Hitler’s visit to Florence in 1938 and that the artist attended along with the different organisations of the Italian Youth of the Lictor of Bologna.

Red dye was poured into the water, a white flag was raised on a pole and its end dunked into the water, where it slowly absorbed the red dye. The symbolic blood of the pool built in honour of the Führer, as well as the slow agony of the artist’s canvas, are metaphors for the way in which thought and culture are oppressed and distorted by two dictatorships.

The blood-soaked white canvas has a further symbolical value: it also refers to the painful times of the Years of Lead, vividly remembered by intellectuals and artists.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 218.

Photo: Gian Piero Frassinelli, 1980.

ENTARTETE KUNST, 1985

Oil on canvas and bronze sculpture

Entartete Kunst [Degenerate Art], the exhibition presented at the Galleria Mara Coccia in Rome in 1985, deals with the relationship between Art and Ideology, a central topic not only in Mauri’s work, but also in the politics of the 19th century.

Entartete Kunst is the name of the exhibition organised by the Nazis in Berlin, Leipzig, Düsseldorf and Salzburg to display those pieces of art that were considered “abominable”.

In his exhibition, Mauri recreated the original writing on a long canvas: ENTARTETE KUNST, Degenerate Art. Underneath, two large oil paintings, one red and the other yellow. In front of the two monochromes, which symbolise the modern avant-garde, there is the bronze statue of a man: the model for the statue is a picture of Goebbels taken during the opening of the exhibition in Berlin in 1938. Goebbels’s face conveys his contempt for expressionist art: his expression is that of someone who knows what truth and quality really are.

On the side wall, the A of “ENTARTETE” becomes the point of intersection of the exhibition. Besides underlining the ideological error, the letter can also turn into a painting: art can overturn and absorb everything, even the negation of itself. Art can survive to politics and to the environmental policy that surrounds it.

In 1979, Mauri began teaching Aesthetics of Experimentation at the Academy of Fine Arts in L’Aquila, combining theoretical lectures with workshops through which he and his students put together major performances Gran Serata Futurista 1909-1930 (1980), Che cosa è la filosofia. Heidegger e la questione tedesca. Concerto da tavolo (1989) and the re-enactment of Che cosa è il fascismo.

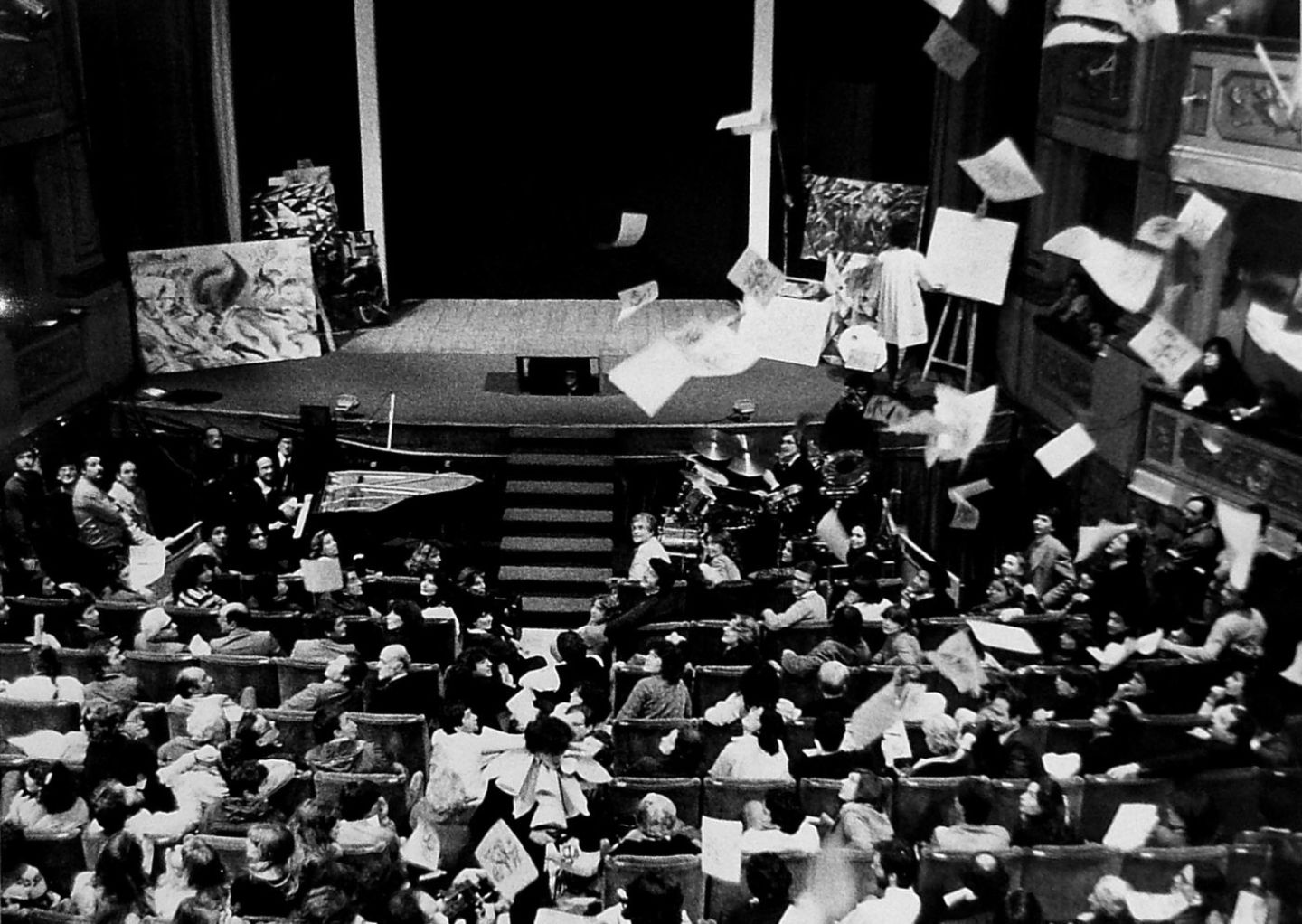

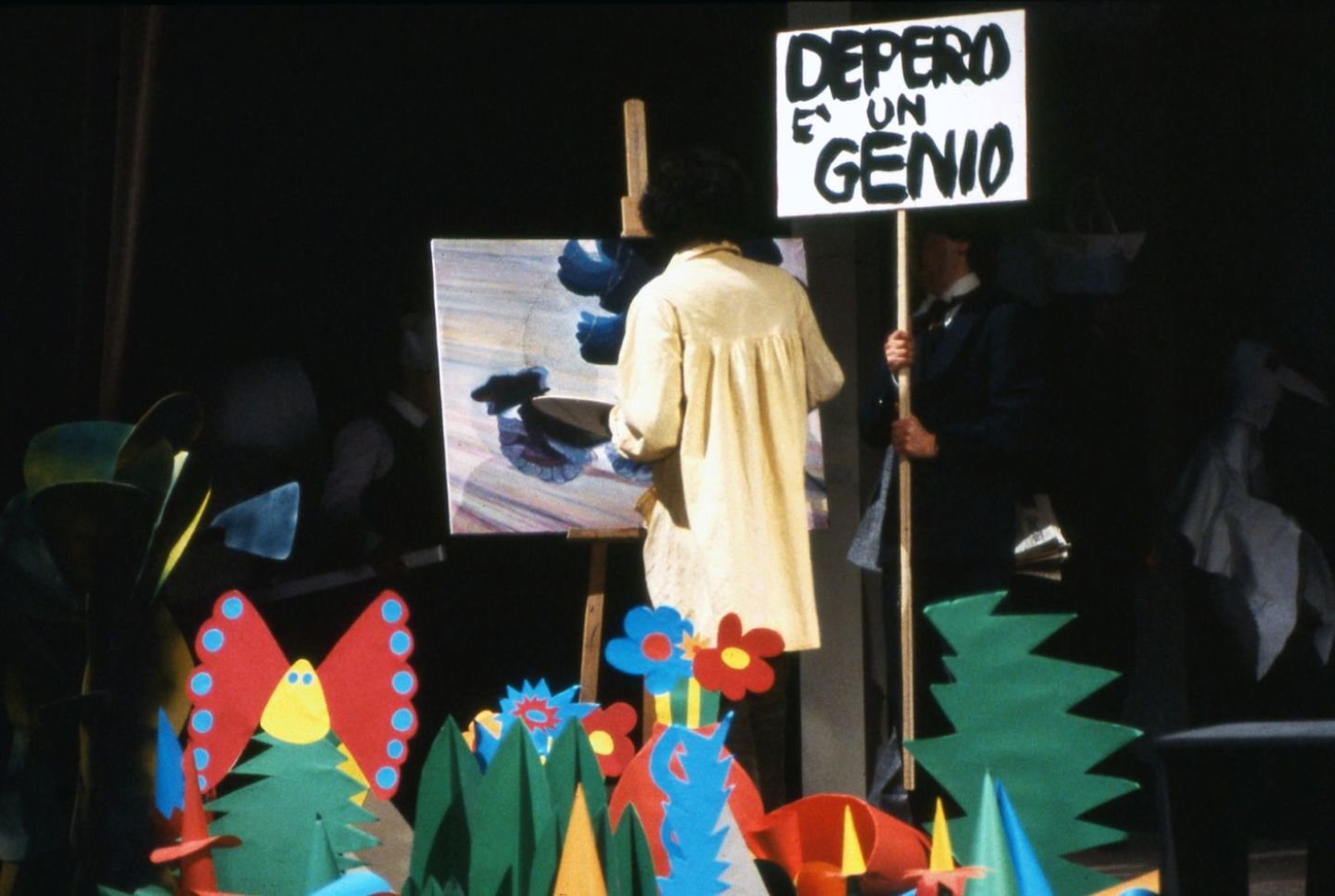

GRAN SERATA FUTURISTA 1909-1930, 1980

Performance

Gran Serata Futurista 1909-1930 [A Futurist Grand Soirée 1909-1930] premiered at the Teatro Comunale in L’Aquila with the students and teacher of the Academy of Fine Arts of L’Aquila and the extraordinary participation of Toti Scialoja in the role of Palazzeschi; Maurizio Calvesi in the role of Critical History; the performer Joan Logue plays Cangiullo’s Poetry in Staves; the dancer Hilary Mostert dances on Marinetti’s words. The arrangements are by the maestro Antonello Neri who interprets Silvio Mix’s and Luigi Russolo’s scores, and Giancarlo Gentilucci is the assistant director. The show is divided into three parts to highlight the various and numerous Futurist languages and inventions, from the period before the war (Interventionism), to the years 1915-18 (life on the front line) up to the post-war years (delusion and dispersion of the Futurist movement). Well aware of the innovations of the historic Avant-garde, Mauri analyses Futurism and philologically reconstructs the texts of the Parolalibero (“freeword”) Theatre and Poems, of Pentagrammata (in staves) Poetry and of Luigi Russolo’s and Silvio Mix’s scores. As example of Futurist Cinematography – rare and almost entirely lost – Mauri projected a short he found at the Istituto Luce in Rome, possibly by Settimelli and Corra. The animation of an abstract drawing whose author may be Balla but whose style is very close to Corra’s, can be seen in the film. The function of the band – which is sometime in the audience, sometime on stage – was to evoke some key episodes: the outbreak of the war, the Futurist funeral, the final victory. There are more than 50 characters, and the show is 4-hour long.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 224.

Photo: © Marcello Norberth, 1980; © Maria Mulas, 1982; © Elisabetta Catalano, 1980.

CHE COSA È LA FILOSOFIA. HEIDEGGER E LA QUESTIONE TEDESCA. CONCERTO DA TAVOLO, 1989

Performance

Gran Serata Futurista 1909-1930, [A Futurist Grand Soirée 1909-1930] premiered at the Teatro Comunale in L’Aquila with the students and teacher of the Academy of Fine Arts of L’Aquila and the extraordinary participation of Toti Scialoja in the role of Palazzeschi; Maurizio Calvesi in the role of Critical History; the performer Joan Logue plays Cangiullo’s Poetry in Staves; the dancer Hilary Mostert dances on Marinetti’s words. The arrangements are by the maestro Antonello Neri who interprets Silvio Mix’s and Luigi Russolo’s scores, and Giancarlo Gentilucci is the assistant director. The show is divided into three parts to highlight the various and numerous Futurist languages and inventions, from the period before the war (Interventionism), to the years 1915-18 (life on the front line) up to the post-war years (delusion and dispersion of the Futurist movement). Well aware of the innovations of the historic Avant-garde, Mauri analyses Futurism and philologically reconstructs the texts of the Parolalibero (“freeword”) Theatre and Poems, of Pentagrammata (in staves) Poetry and of Luigi Russolo’s and Silvio Mix’s scores. As example of Futurist Cinematography – rare and almost entirely lost – Mauri projected a short he found at the Istituto Luce in Rome, possibly by Settimelli and Corra. The animation of an abstract drawing whose author may be Balla but whose style is very close to Corra’s, can be seen in the film. The function of the band – which is sometime in the audience, sometime on stage – was to evoke some key episodes: the outbreak of the war, the Futurist funeral, the final victory. There are more than 50 characters, and the show is 4-hour long.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milano 2009, p. 268.

Photo: Claudio Abate, 2012.

Mauri’s entire oeuvre was characterized by use of often only partially modified objects as subject matter for art: “The objects acquired in my works are commonplace in world phenomenology, yet they are also magnets of history, their historical delusions immediate,” wrote the artist.

A few examples of Mauri’s artistic research based on constantly deciphering/reconstructing the sign-like whole that is reality are: a pantograph used for his statues at the Mole del Vittoriano in Rome transformed into a Macchina per forare acquerelli (1990), suitcases in Il Muro Occidentale o del Pianto (1993), objects and knick-knacks at the ‘Ariano’ exhibition (1995), or as focused on in his Autobiografia come Teoria (1997) and Pic-nic o il buon soldato (1998) pictures, and furniture from Rebibbia prison (2006).

IL MURO OCCIDENTALE O DEL PIANTO, 1993

Suitcases, bags, cases, leather cases, canvas, cardboard, wood, metal, discs, water bottle, umbrella handles, paper prints, potted ivy plant

400 × 400 × 60 cm

Il Muro Occidentale o del Pianto [The Western Wall or the Wailing Wall], presented at the 45° Venice Biennale in 1993, is a 4 meters long wall made of leather and wooden suitcases of different dimensions which represent world’s division, exile, escape and forced exodus. The suitcases of Il Muro Occidentale o del Pianto are the luggage of immigrants and emigrants who were not necessarily victims of the Holocaust.

On the front, the suitcases create a balanced and regular architectural structure; on the back, on the other hand, the structure is twisted, plastic, and the suitcases create layers and gaps, as it happens with human nature.

Inside the holes of the Il Muro Occidentale o del Pianto the Jews stick scrolls of parchment on which they have written prayers for their loved ones, their souls, their bodies, and prayers on how to live life on earth: for the Jews, the Wall is where God is always listening.

In his Wall, Mauri reproduced all these prayers on a single roll of white canvas, which represents a sort of “prayer of art”. There is an ivy twig inside a jar which symbolises that no slaughter can kill Art, here seen as the deep and rightful Man who believes in Man.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 312.

This work contains a photograph by © Elisabetta Catalano of Fabio Mauri's performance Ebrea, 1971.

Photo: Graziano Arici, 1993.

Video: Dario Bellini, 2020.

MACCHINA PER FORARE ACQUERELLI, 1990

Pantograph in iron and wood, watercolor on corrugated cardboard, coins

370 × 160 × 290 cm

Macchina per forare acquerelli [Watercolour-piercing machine], presented at the Studio Bocchi in Rome in 1990, is a big pantograph whose fixed ends pierce in their centre two watercolours made by the artist on a grosgrain canvas. Two one-hundred-lire coins of different sizes are fixed to the ends of the pantograph to symbolise the swings of the purchasing power in the relationship between art and market, and the lack of connection between size and value. In the same space there is another identical, tiny machine.

The visual interaction of the two pantographs expresses the symbolical function of the pantograph itself: the “disproportion” between the work of art and the object it represents.

Art’s absolute anarchy is minutely and openly recreated.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milano 2009, p. 300.

Photo: Claudio Abate, 1990.

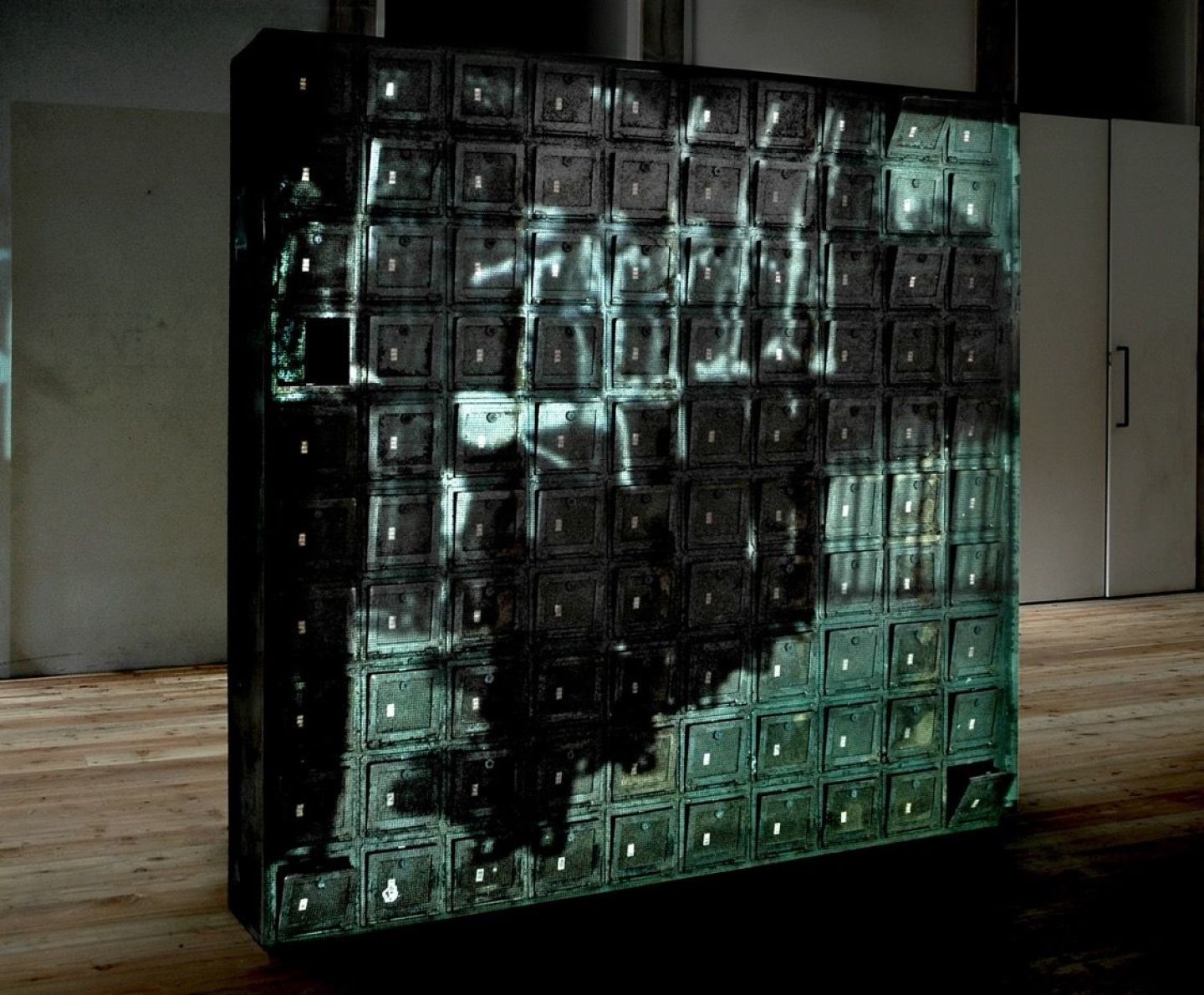

REBIBBIA, 2006

Digital projection on iron furniture, projector on iron base with graphite patina

197,5 × 190 × 30 cm

The work Rebibbia, presented at the Galleria il Ponte in Rome in 2007, is a chest of several and small half-open iron drawers. These drawers represent the lives that have been lived and lost, as if evaporated, on which Mauri projects the film Ballad of a soldier, directed by Grigory Chukhray. This film is projected onto different works. The plot is complete: life, joy, pain and death are perfectly mixed. The drawer is an old piece of furniture found in the Roman jail Rebibbia, whose painful history is connected to the Nazi occupation. The events of the war, here interwoven with ordinary and common lives, underline the significance and the relevance, until when its “actors” disappear, of a modern existence witnessed thanks to an undeniably true account.

Rebibbia is a new type of work displaying a kind of expression developed thanks to the Proiezioni of the mid 1970s, i.e. the projection of art films on unconventional “screens”, properly or improperly historical.

Dora Aceto in Fabio Mauri, Io sono un ariano, Lampi di stampa, Milan 2009, p. 452.

Photo: Sandro Mele

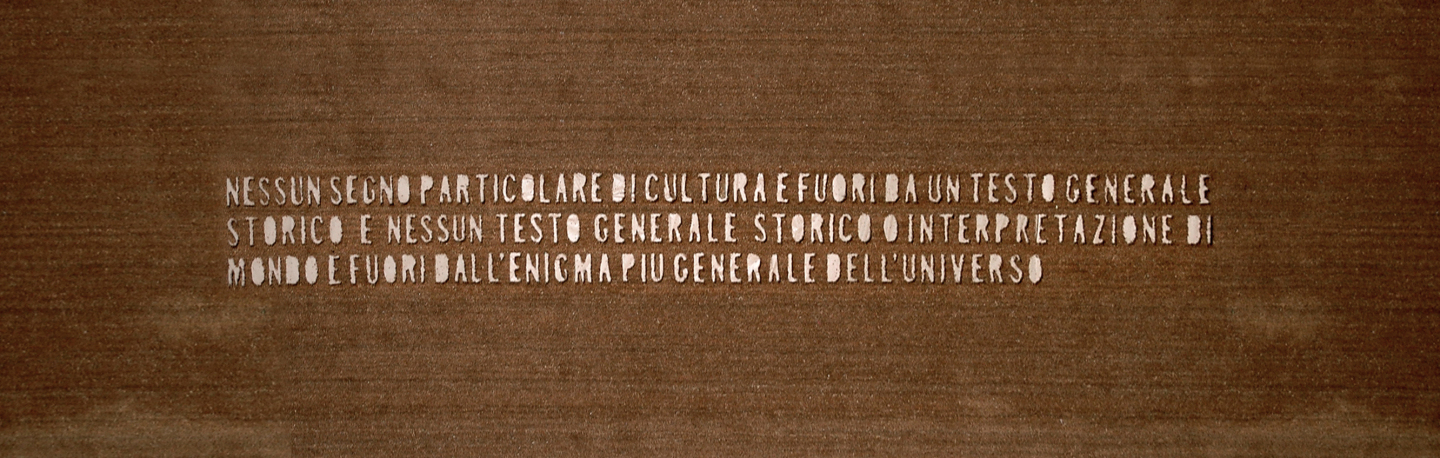

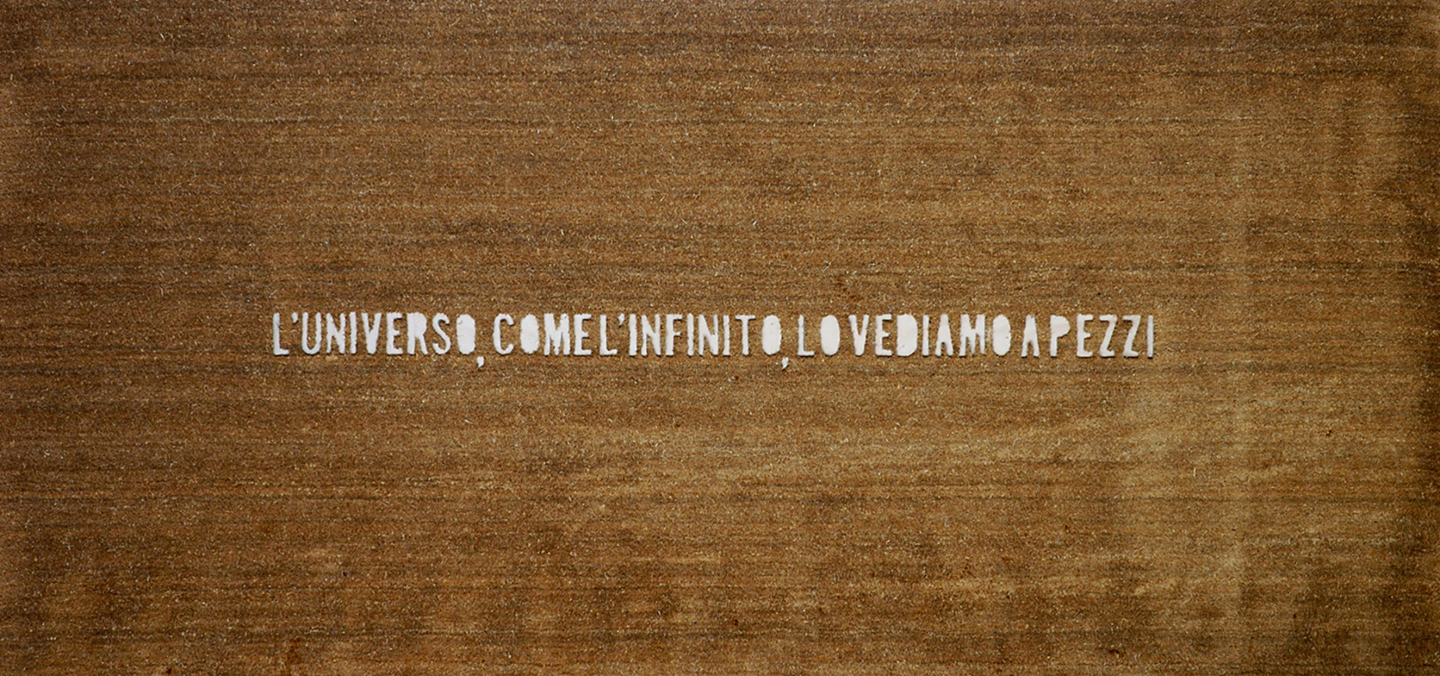

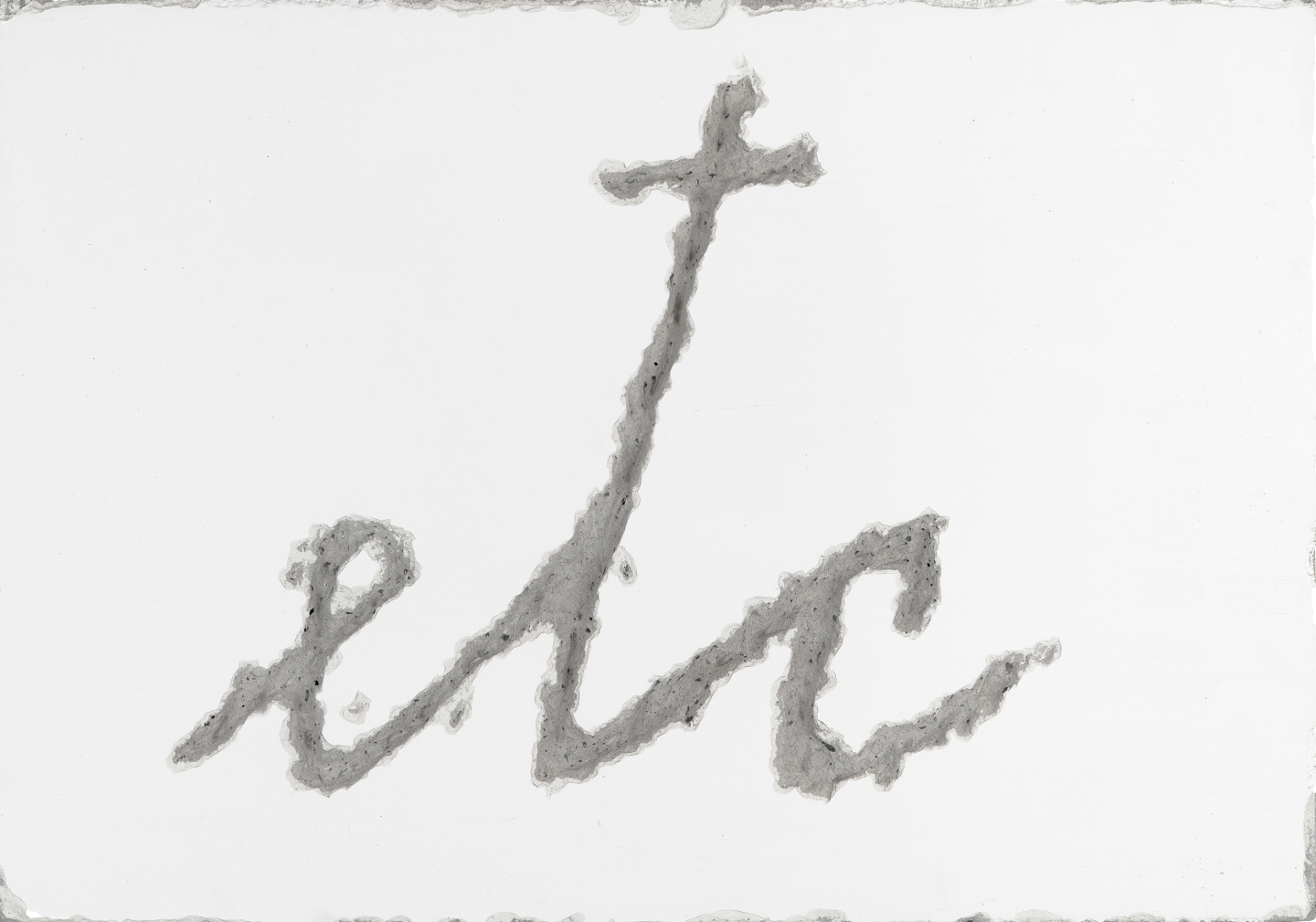

In the 2000s, the written word took centre stage in a number of the artist’s works, painted on paper, printed on carpeting, carved on walls, and etched into objects.

In his final solo show, the audience was invited to step onto five large doormats with statements etched into them. Opening two weeks after the artist’s death, the exhibition was significantly titled Etc., a word inscribed on a plastered concrete block displayed in the gallery’s central hall.

NON ERO NUOVO, 2009

Cutting on doormat

201 × 420 × 1,8 cm

Some of the works are: Lo zerbino ariano [The Aryan doormat], Studio Bocchi, Rome, 1995; then the L’ospite armeno [The Armenian guest], Venice, 2001; and also Lo zerbino Insolubile [The insoluble doormat], galleria Martano, Turin, 2008.

Mauri scatters thoughts, words, considerations across the floor, and the audience can read and walk on them. They are a metaphor for our incomplete mental processes. They are meaningful because they are inside the thought: when walking on them, it is not possible not to be inside their meaning. The Zerbini show signs of daily reflection. They reject, but, at the same time, they bring us closer to experiencing something which is similar to the real state of things, i.e. to a truth which is always a metaphor for larger or smaller, shorter or more certain truths.

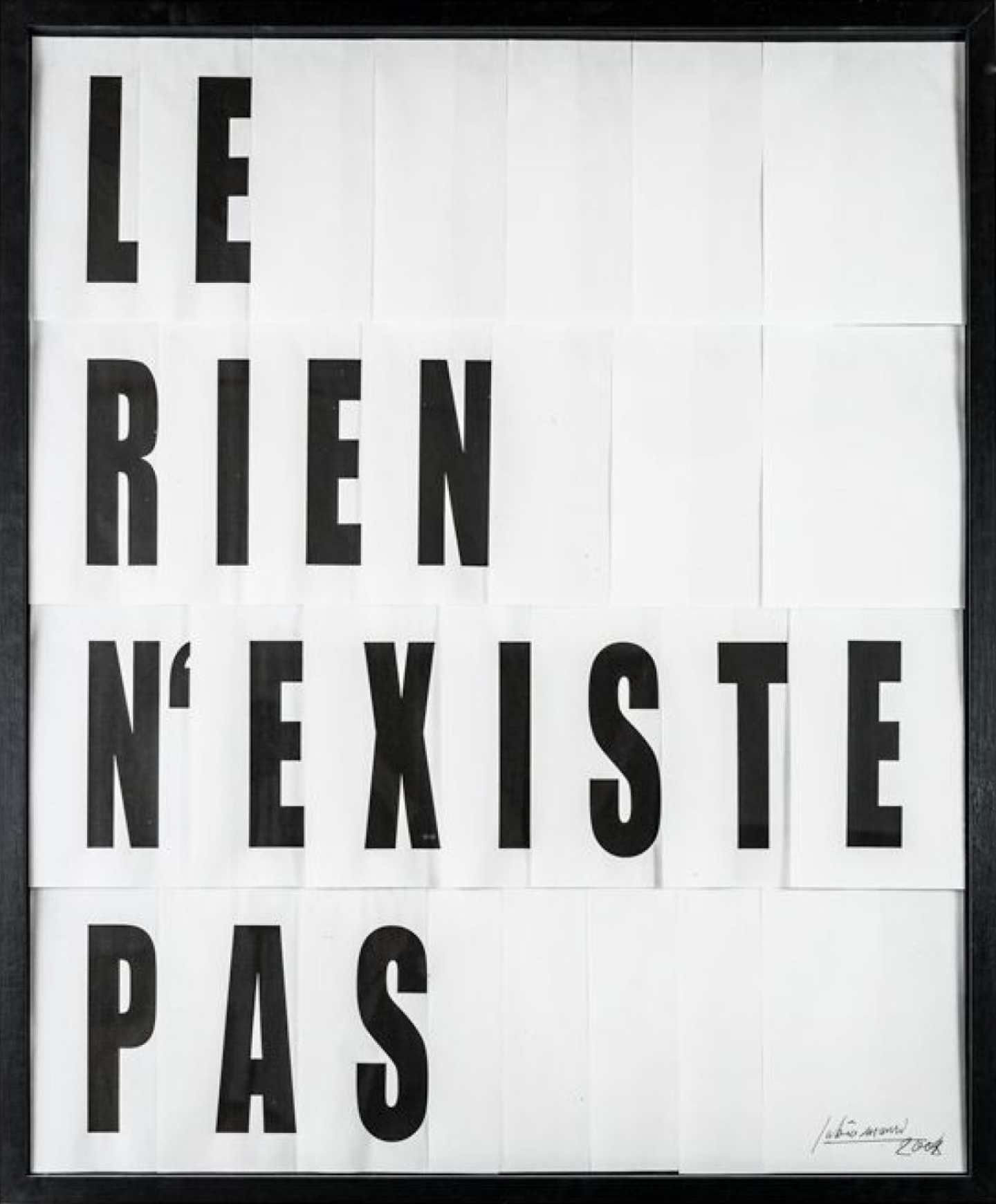

LE RIEN N’EXISTE PAS, 2008

Digital prints on paper, collage on wood

125 × 103 cm

ETC, 2009

Incision on plastered cement

68 × 98 × 9 cm

WOULD YOU LIKE TO LEARN MORE, SEE MORE OR DO RESEARCH? ACCESS THE CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ EDITED BY CAROLYN CHRISTOV-BAKARGIEV

Catalogue Raisonné Catalogue Raisonné